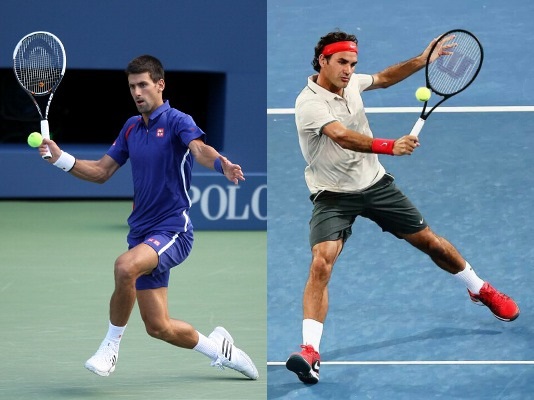

There has never been a better rivalry in tennis than Federer-Djokovic. Certainly there have been better stories, such as flamboyant Agassi vs the stoic Pete Sampras. Combined with their warring personalities, Agassi and Sampras embodied visibly different tennis ideals – the powerful serve and volleyer and the baseline blaster. That is not to say there is no contrast between Djokovic and Federer. Djokovic tries so visibly hard to be loved, when Federer has become the most beloved player of all time with seemingly so little effort. Federer plays with attacking flair, while Djokovic is almost machine like in his clinical defense. It is Maestro vs Machine.

They have dueled 45 times over the span of 10 years, with Djokovic winning 23 times to Federer’s 22. Their matches have evolved over time as their games have evolved. They first met during Federer’s prime in 2006, and unsurprisingly the Swiss had the better of those early meetings. He could outhit Djokovic from the baseline, had a far superior serve and fully developed net game (something Djokovic still lacks). But time changes all things, and tennis players are no exception. Somewhere in the intervening years, Federer lost a step but his net game continued to improve. Meanwhile Djokovic quietly turned himself into one of the fittest athletes on the planet, evolving into a defensive juggernaut with the ability to finish points off the ground.

Today we will look at the matchup as it stands today, and then in the two articles to follow examine their two biggest meetings in 2015 – the Wimbledon and US Open finals.

Serve

This is one area where traditionally Federer has had the clear edge. The Swiss has changed his motion over the past decade, and it quietly evolved into one of the best serves on tour (it was pretty good to begin with). In truth from a technique standpoint it might be the best serve on the tour. Meanwhile Djokovic has had serving issues in the past. He is susceptible to double faults in some big moments, something that hasn’t entirely gone even as his second serve has improved. Djokovic generally is content to hit a less aggressive serve than Federer, which is reflected in his higher first serve %, but lower ace count. In 2015 Djokovic made 66% of his first serves, but hit aces on only 11% of them. Federer made 64% but hit aces on 18% of them.

Harder to measure is the quality of their second serves. Since second serve points tend to start off far more neutral than first serve points, the rate of victory on the second serve delivery is often more a reflection on the player’s baseline game than it is on the quality of serve. Federer’s second serve averages 5-6 mph faster than Dkokovic’s, and appears to have more spin (although there’s no data out there to confirm that. The ATP does not publish data on double faults, but when we look at individual matches, Djokovic does have a higher double fault rate so between the extra velocity and lower double faults alone we can safely say Federer’s second serve delivery is superior.

Forehand

During his prime, Federer’s forehand was perhaps inarguably the greatest forehand in the history of the sport. His ability to hit spin approaching or matching Nadal’s, yet also flatten it out like del Potro gave it a utility that was unmatched. His forehand isn’t quite the shot it used to be, but is still an incredibly formidable weapon. Djokovic’s forehand is no slouch either, but it is a shot built for the higher ball. Djokovic thrives around shoulder height on both wings – something which helps him immensely when playing Nadal.

While Federer has the advantage on this wing overall, there are two areas where Djokovic performs exceedingly well off the forehand. The first is when stretched very wide. This is in part due to his sublime footspeed, but when pulled wide on the forehand wing Djokovic’s ability to rocket the ball back cross court with sharp angles is matched only by perhaps del Potro and Federer. He doesn’t open the court up well himself, but when someone opens it for him… watch out.

The second is the mid-court ball. As mentioned earlier, his stroke is perfect for the shoulder-height ball, and when he gets a ball in the middle up high he can take in either direction with excellent disguise. This is something that becomes critical in their match-up at Wimbledon this year.

Backhand

While Djokovic might not have the best backhand in the history of the game, it is certainly very, very, very good. It is such a clean stroke, and combined with his movement and ability to change direction he outplays Federer by a huge margin off this wing. Critical is the fact that even when pulled very wide out to his backhand side, Djokovic is still able to pull the ball back solidly cross-court. It is this, perhaps even more than his backhand down the line, that has allowed him to dominate the men’s game in 2015.

Federer’s backhand has been the talk of tennis for many years now. Once lauded as a beautiful shot (which it still is), it is now often criticized as his Achilles’ heel. He has always struggled somewhat with the high ball above the shoulder on this side when trying to hit topspin, but the truth is his struggles on this side in the last 5-7 years are more related to his movement than anything in the stroke itself. Having lost a half to a full step on the court, Federer gets caught late on this shot more than he’d probably like to admit, and in doing so either makes errors or hangs the ball in the center of the court.

Volleys

This is probably the area where Federer’s advantage is greatest. He was always a good volleyer, but over the last 10 years between the tutelage of Annacone and then Edberg, his volleys are now truly at an elite level. With the retirement of Llodra (and perhaps even without it) he is left standing alone among volleyers in the top 100. His overhead is the best in the game – so much so that throwing up a lob is tantamount to giving up.

Meanwhile Djokovic struggles mightily at the net. Along with Agassi he is probably the worst volleyer to reach #1 in the Open Era. His technique is poor, and his overhead at times miserable. We have seen some improvement in his net game since he hired Boris Becker on as his coach, but he still leaves much to be desired in the front of the court.

Return of Serve

Federer has long been a great defensive returning. During his prime he had an uncanny ability to blunt the big serve of his opponents. We saw it time and time again against players like Roddick and Philippoussis (Roger’s first Wimbledon title) where an opponent had been blasting 20+ aces per match all the way through a tournament, only to serve 3 aces against Federer. However one area that’s long been lacking is his ability to be more aggressive off the return. To be sure on occasion he can run around his backhand and punish a forehand like nobody else (something he does less these days), but in general terms especially off the backhand wing Federer has traditionally been very passive on the return. His adoption of the so-called “SABR” in the past few months is obviously an attempt to mitigate this, and it has proven very effective for him in helping turn the tide of matches.

Djokovic suffers no such limitation. Among the great returners in the history of the game, Djokovic is highly effective both as a defensive returner and an offensive returner. He has proven himself able to fire blistering returns off first serves and to be able to attack second serves off both wings. While his defensive returning perhaps doesn’t quite match up to that of Federer in his prime, Federer’s skills in that department have degraded somewhat and Djokovic holds a decisively clear edge in the return of serve.

Movement

Something we talk about very little when discussing movement in tennis is technique. There’s a huge focus on athleticism, footspeed and explosiveness. And yet there is a significant amount of technique involved in movement. Djokovic presents an interesting conundrum in this area. He is at this stage undoubtedly the greatest lateral mover in the history of the sport. His ability to sustain explosive movement side to side over extended periods of time is unmatched. Having said that his vertical movement (up towards the net, back for overheads etc) doesn’t even approach his lateral performance. Some of this may be related to the fact that his movement technique at times is less than ideal. For such an elite athlete, he falls on the court a surprising amount.

Contrast this with Federer, whose movement has been described in almost poetic terms over the years. He almost seems to float around the court, and the idea of him falling feels almost absurd (it has happened, but it is incredibly rare). Federer’s movement technique is immaculate – his foot placement stride length virtually without flaw. However there is no doubting that he has lost some court coverage over the last decade. He is between a half a full step slower across the court than he was during his prime and this plays a huge part in his match-up with Djokovic.

Djokovic carries away the clear edge in the movement category of their match-up. He outstrips Federer in lateral movement, and although his vertical movement isn’t as crisp his style of play makes that almost irrelevant. Djokovic is faster side-to-side, and has more endurance than Federer.

Strategical and Tactical Preview

One of the things that makes the match-up between Djokovic and Federer so compelling is that neither’s game inherently gives him a clear advantage over the other. Federer’s advantages in the serve, forehand and volleys are negated beautifully by Djokovic’s superior return, movement and backhand. What we are left with a subtle jockeying for position as both players strive to use familiar patterns to impose their overarching strategies onto the match.

Djokovic’s Tactics

Djokovic’s plan is really quite simple. He’s essentially waiting for Federer to expose himself through a single poor shot or decision. Djokovic feeds off the rhythm of long rallies where his amazing level of conditioning can truly shine. He loves moving laterally, and is at his absolute best when he gets pulled wide, the other player creating the angle for him and opening the court up.

Djokovic is content keeping the ball mostly cross-court, although he will favor balls to Federer’s backhand when it suits him. However he is one of the few players happy to stay in the cross-court forehand rally with Federer, because his movement is so superb that the wider Federer pulls him on that side the more dangerous he becomes.

Ultimately Djokovic is jockeying for a high, slower ball in the center of the court. On this shot, particularly on the forehand Djokovic can freeze Federer, and finish the point. He sets this up typically in three ways.

- Taking his backhand down the line off a Federer cross-court backhand. As Federer’s movement isn’t as fast as it was 10 years ago, he can catch Federer late on the forehand and get the center ball

- The backhand cross-court off a Federer down-the-line forehand. Again capitalizing on Federer’s decreased movement, when Federer tries to hit over that backhand on the run he tends to hang it in the center of the court

- The cross-court forehand from a wide position off Federer’s forehand. As mentioned earlier the wider you pull him the more dangerous Djokovic becomes. When Federer pulls him wide on successive forehands Djokovic can fire the ball hard and wide and draw a weak reply

This ball is critical, because Djokovic isn’t a strong finisher at the net. By playing for the mid-court forehand Djokovic can end the point on his terms with one of his best shots.

Federer’s Tactics

Federer has an entirely different set of goals. For him Djokovic is a wall that he must forcibly break down. He cannot afford to be too patient, because Djokovic will punish him for small mistakes. His entire strategy against Djokvic centers around denying the Serbian a rhythm. Short points, aggressive play. First serve then a forehand. Get forward into the net.

Federer’s game has always been centered around his serve and his forehand. Against Djokovic it is doubly critical these days because Federer simply cannot afford to get stuck in backhand exchanges. This is for two reasons. First is Federer’s slightly diminished movement – running around the backhand to hit forehands is harder than it once. This is compounded by Djokovic’s excellent backhand down-the-line. If Federer creeps too far out of position he will get punished. The second is that Federer’s patterns to get himself off the backhand aren’t as intelligent as they were 10 years ago. Again the movement plays into this, but Federer used to use his slice backhand to devastating effect to change the flow of play. He could go from being trapped in his backhand corner to hitting attacking forehands in 3-4 shots. These days too often he gets trapped there and simply cannot find his way out.

Hence Federer has to serve well, and he has to use the serve particularly to get a forehand for his first ball. When constructing points well against Djokovic he moves the ball frequently around the court, but keeps things slightly more central than he might against other players. A cross-court forehand is followed by a forehand into Djokovic’s backhand – but not truly into the corner because that opens up the space for Djokovic to get the ball across into Federer’s backhand. He’s playing for the shorter ball he can come in behind and use his net skills to end the point. Djokovic is great on the run, but he doesn’t pass the way that Nadal did during his prime, combining his bull-like strength with heavy topspin to hit dipping, high velocity passing shots from even the most extreme positions.

Conclusion

It truly is a matchup for the ages – two largely complete players with different styles battling on the biggest stages in tennis. What follows next in this series is an examination of their two biggest matchups in 2015 – the Wimbledon and US Open finals. We will look at what Federer almost did right, and the patterns that cost him the titles.

Remember you can follow Tactical Tennis on Facebook!