One of the major focuses of this article series are the tactical patterns the Federer employed during his prime. It isn’t enough for us simply to say that Federer is a great player – that he has an amazing serve, an imposing forehand etc etc. Many players have had a plethora of great shots but failed to connect the dots. Success comes from a player having repeatable patterns of play they can utilize to win points, almost like a recipe for a dish. A great player has access to many different patterns on the strength of their many weapons and skills. Some of these patterns (or recipes) will be successful in the absence of one, or even two of the players best weapons. This is how great players are able to be successful on even their bad days – they have pre-established patterns of play that they have practice and executed hundreds and thousands of times in the past that allow them to adapt to the changing circumstances of the match they are currently playing. Federer’s serve, forehand and backhand were all good in 2001, 2002 and 2003. But it wasn’t until 2004 that he finally put all of the pieces together and was able to consistently employ patterns to deal with a wide variety of opponents and in doing so dominate the circuit.

At a glance when we examine the weapons that Federer has at his disposal, it might seem odd to begin a series examining Federer in his prime with the slice backhand. However in many ways the slice backhand is a key component of Federer’s success, and as we will see his reduced use of the slice has contributed to his performance over the last several years. As Federer’s game has become more and more aggressive by nature, his performances have become increasingly erratic. At times we have seen flashes of the brilliance that Federer would routinely dazzle us with. Yet there have also been lackluster performances, the Federer Express chugging to a halt under the weight of too many shanked forehands.

The artistry of Federer’s game is something that has been discussed often, and his deft use of the slice backhand has played a huge role in that perception. The versatility of the shot is astounding. Off the same ball Federer could hit a driving slice approach shot or a vicious drop shot that bounced sideways upon touching the ground. In days of old he would diffuse his opponent’s pace, pull them into awkward court positions and extend rallies – all with the slice backhand. And yet as time has progressed, Federer has gone to the slice less and less. These days he uses it largely defensively – when forced to due to being rushed by an opponent. It appears he feels pressure to hit over the backhand and impose himself more with it, and in doing so he has lost one of his most effective patterns that helped him to dominate the game earlier in his career. In today’s article, we will focus on a specific shot Federer would frequently play with his slice backhand that set up in fact multiple patterns of play for him: the short slice.

Forcing Difficult Decisions

When you’re a professional tennis player, you spend somewhere between 2 and 6 hours hitting tennis balls pretty much every day. As you can imagine you get quite good at it, and fairly quickly you reach a place where unforced errors become a relatively rare thing. One need only go back and look at the Monfils vs Simon farce from earlier this year to get an idea of the level of consistency good college players and pros obtain when they’re happy to just make balls. Where this gets interesting (and relevant) is that in order to win at high levels of tennis, you cannot simply hit a lot of balls into play and wait for your opponents to miss. Players are too athletic, and just downright too skilled for that to be sufficient.

And so high level chess becomes like chess. Points, games and matches are not won in simple terms. When two highly skilled chess players face off, the battle is not just about pieces but about position. Winning doesn’t happen in a single bold stroke, but by the accrual of small advantages. If you can get a slight advantage over your opponent, you can use that advantage to pressure them into an even bigger advantage. In tennis it all happens very quickly, but the same principle applies. It is not enough to hit the ball hard, or deep, or with heavy spin. You must force your opponent into a place that is uncomfortable – where they must make difficult decisions.

Nadal does this quite obviously with his forehand. He is quite content to hit brutally heavy topspin forehands into a right-hander’s backhand repeatedly. Why? Because in doing so he forces them into a difficult decision. If they stand back on the ball, they end up hitting above their shoulders from deep in the court over and over again. This isn’t just fatiguing – both players know it is only a matter of time before one of those backhands falls short in the court and Nadal will step up and punish it. However what are the other options? Play the high risk ball down the line? Step up, take this heavily spun ball on the rise and try to outhit Nadal cross-court? You quickly realize that unless you are possessed of a very specific skillset on the backhand side, there simply are no good options in this scenario. Nadal puts his opponents in a position where they must try to choose from among the lesser of not just two, but several evils.

The Short, Low Slice Backhand

Federer does much the same thing with his slice backhand, but does so in a way that is far more subtle. The shot that Federer mastered, and used to use often to great effect was a short, low slice backhand. This shot has an incredible amount of backspin, it stays low to the court and bounced twice before the baseline. Now don’t confuse it with an actual drop shot for it was nothing of the sort. This ball had a low, flat trajectory, and was coming through the court. The first bounce was typically inside the service line, the second somewhere between the service line and the baseline. On paper it sounds relatively benign but it was in truth a critical part of Federer’s arsenal. The ball is too low for most players to hit over it successfully with any level of aggression. This forces them to mostly play with a shot that is very under-developed and under-used in today’s men’s game – the slice backhand. So let’s pause for a moment and consider the situation his opponents now find themselves in. They are standing a couple of feet inside the baseline, on the ad side of the court. The ball is down below their knees, they are stuck hitting one of if not the weakest shot in their arsenal, and on the side of the net is one of the greatest movers and ball strikers in the history of tennis. As you might imagine, this opens up multiple patterns of play that are all in Federer’s favor. Let’s rewind the clock to the 2005 Australian Open semi-final match between Federer and Safin (ironically a match Federer lost despite holding match points) and take a look at some of them…

Scenario 1: The Cross-Court Approach

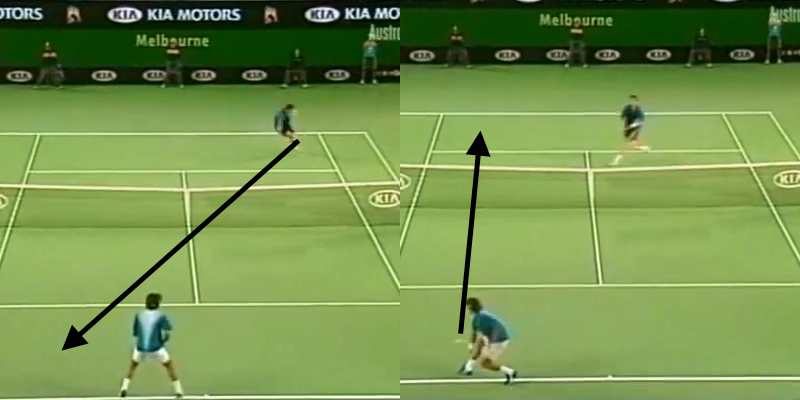

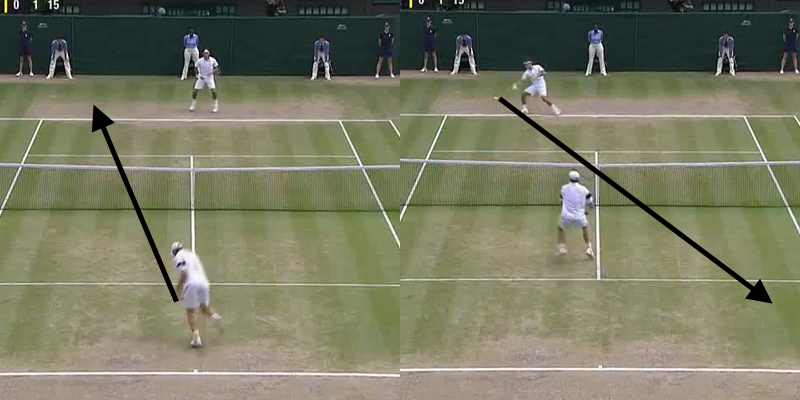

One of the most common responses to this ball from Federer is the cross-court approach. On the surface it isn’t a bad play – hitting into the weaker side over the low part of the net into the longest part of the court. The problem is that Federer’s backhand as at it’s best on passing shots. So inevitably we are left reminded as to why we are taught to almost always hit our approach shots down the line:

Playing the cross-court approach poses two very real problems. The first is it opens up the passing shot down the line. You can see in the left hand frame that Safin is making contact near the right sideline. From this position he must then move diagonally forward to cover the left sideline to prevent the pass that takes place in the right hand frame. The second issue is you can see in the right frame Safin’s body positioning at the point of contact from Federer. He is biased to his right (your left) – his hips and shoulders are turned, and he is in mid step. If Federer were to go cross-court instead, Safin is not situated to stop and hit the ball that is now going behind him. Certainly he could have chosen to square his hips up and split step, removing that bias but if he did so Federer would have the easiest passing shot imaginable down the line as Safin would have no real play on the ball. Safin is forced to bias himself simply to cover the ground necessary.

Scenario 2: The Down The Line Slice

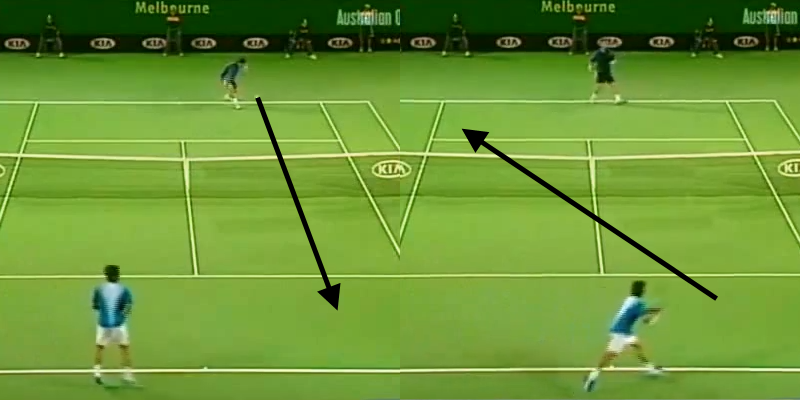

Having learned not to come in behind this ball, Safin uses the slice down the line to try to pull Federer out of position and earn himself a forehand. Against many players this would be a very effective play. However Federer uses a slightly modified eastern forehand grip, which allows him to handle the low ball off the forehand better than most who use semi-western or even western grips.

The reply is both swift and final. Federer breaks quickly up to the ball and rips it cross-court for a clean winner. The video changed angles at the point of contact, but suffice to say Safin was again in perfect position when Federer struck the ball – bisecting the angles of return and using a textbook split-step. Despite this he barely even broke for the ball before conceding the winner to Federer.

Scenario 3: The Cross Court Slice

Despite his volatility, Safin had a very complete game. After being burned by the other two plays, he instead tries to return the short slice back cross-court into the Federer backhand corner. This is one of Federer’s favorite patterns because it instantly gives him almost complete control over the point:

Federer runs around his backhand in this situation, and now he’s hitting his forehand from the ad court – something he is very fond of doing. You can see in the frame on the right that he really has a huge spread of possible shots he can play off this ball. Safin in fact takes up excellent position, almost perfectly bisecting the possible angles of return and you can see he is a neutral, balanced position. It does him no good. In the point in question, Federer hits the inside out ball, pulling Safin off the court to the backhand and then hits a drop-shot winner to the opposite side off the very next ball. Part of what makes this such a great option for Federer is that Safin must retreat not only towards center but also backwards in order to regain his court position. This makes him especially susceptible to the angled inside-out forehand that Federer ultimately hits during this point.

Scenario 4: Down the Line Approach Shot

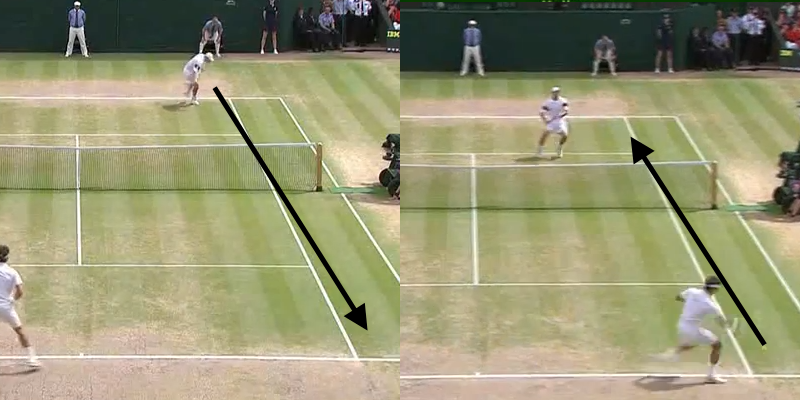

It is not surprising that I couldn’t find an instance of this taking place during the Safin-Federer match. From early on Federer established his forehand passing shot as one of the most formidable in the game. Playing the ball down the line on Federer in this instance for most players is tantamount to conceding the point. For a quick sample, we will jump ahead four years to the 2009 Wimbledon final between Roddick and Federer:

While Roddick is no Patrick Rafter, in this instance he hit about as good of a down-the-line approach shot as one could hope for under the circumstances. It was low, skidding through the court and yet Federer was there in time to hit a nasty curving shot down the line. Roddick actually covered it well, but Federer than ran down his volley and hit a backhand passing chip down the line for the winner. Of course Federer is also capable of easily going cross-court as we can see here:

In this sequence Federer has pulled Roddick into a more central position with the low slice. Roddick plays a respectable ball out into the Federer forehand and pays the price when the ball is spun past him cross-court.

Is This Feasible In The “Modern Game”?

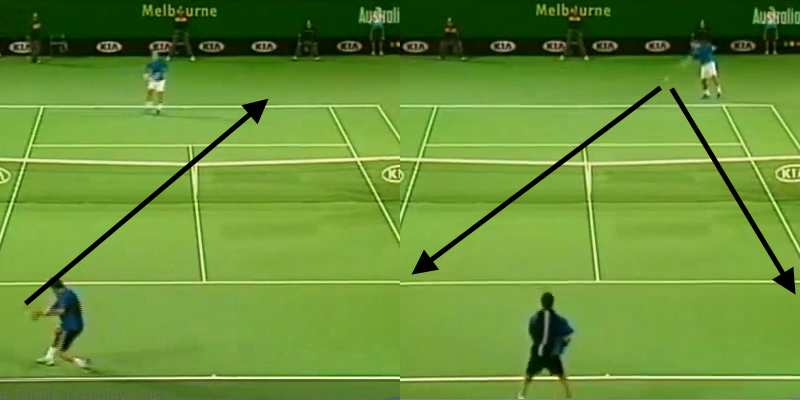

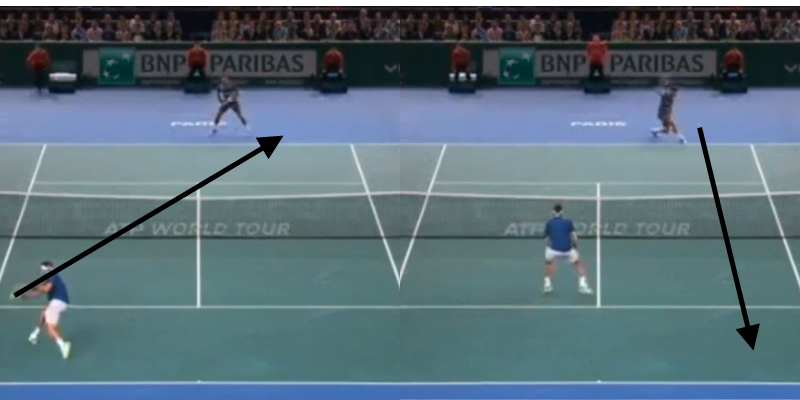

It seems almost funny to ask and answer this question, but given how much Federer has moved away from this particular shot to favor his topspin backhand in recent years it bears asking. Surely the “Greatest of All Time” wouldn’t abandon a winning strategy for no reason, right? Just yesterday Federer beat del Potro in the Paris Masters in what might prove to be one of the biggest wins for him this year. In fact, it marked the second time in 2013 that Federer had beaten a top 10 player. Ironically given the timing of this article, it was largely the slice backhand that made the difference for him. Let’s take a quick look and see if we can recognize any of the patterns from above:

Look familiar at all? Del Potro has a nice slice backhand, and with his height is no easy person to pass at the net. One thing I do want readers to note is del Potro’s body positioning in the right hand frame. Remember above when we looked at Roddick fall for this same pattern we talked about his body alignment. Here del Potro actually does square up his hips and split step in the classic style. We can see just how little of the line he is able to cover in doing so, and the winner that Federer hits as a result is far out of del Potro’s reach.

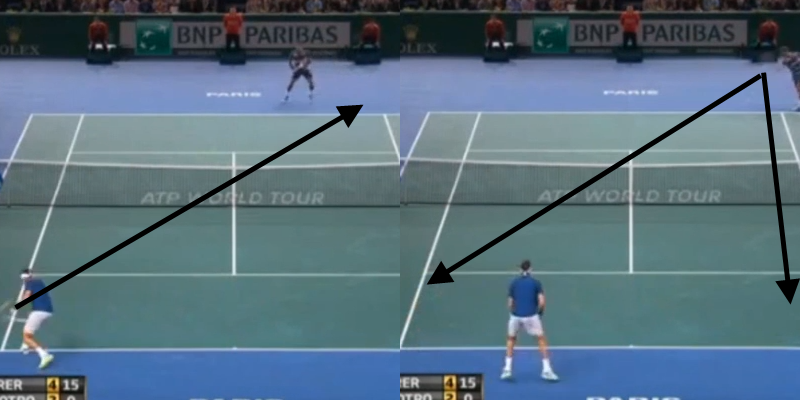

Here del Potro uses the cross-court slice, and Federer runs around it to set up the forehand. Again look at the possible spread, and when he takes the forehand inside-out as he did against Safin, he pulls del Potro out of position and sets himself up to win the point a few shots later.

The match against del Potro was certainly a fascinating one. Federer used his slice backhand to good effect for the entire first set and won it fairly comfortably. Then he inexplicably abandoned the slice during the second set (which he lost) until early in the third set. In the third set, Federer once again used the slice and reeled off a string of points to seal the victory. Obviously this wasn’t the only facet of his victory, but given how small the margin between victory and defeat is at that level it was certainly the tipping point in Federer’s favor.

In short the answer is a resounding yes. The short slice backhand isn’t just feasible at the highest levels of the game for Federer, it is virtually essential. The change of pace it provides, and the multitude of positive patterns of play it sets up for the Swiss Maestro makes it an essential piece of his arsenal.

Conclusion

There is much that even recreational players can take away from this shot. The first is just what a big role patterns play in tennis. The ability to fall into a familiar routine that leads to winning the point simply cannot be overstated in its importance. The second is just what a four-dimensional sport tennis is (depth, width, height and time). Tennis has become very one-dimensional at the highest levels, with players mostly tracking side to side laterally three to five feet behind the baseline. The ability to move someone away from this East-West pattern of movement into a North-South one can be critical in disrupting your opponent. Sometimes there is too much focus on depth, topspin and power when it is often the counterpoint to these three that makes the difference.

Federer still has all of the tools he needs to compete successfully for Grand Slam titles. The question isn’t whether or not Federer can win another Slam. Rather, it becomes a matter of whether or not he can set aside his stubbornness and make use of the many and varied patterns and tools that made him such an unstoppable force for so many years. The depth of Federer’s game is what set him apart and until he is willing to use that depth to show his opponents things that they are lacking, and to better control the flow of points he is going to struggle.