When Wawrinka held aloft the Australian Open trophy it was the culmination of years of sitting on the cusp of a breakthrough. There were hints of course – the two epic five set matches against Novak Djokovic at the Australian and US Opens in 2013 for one. Long possessed of one of (if not the) finest one hand backhands in the game, Stanislas Wawrinka finally stepped out of Roger Federer’s shadow, doing so with an exclamation point by beating Nadal in the final a mere two days after Federer fell to the Spaniard himself. While some Nadal fans point to his injury as being the deciding factor in the final, Wawrinka was clearly outplaying Nadal right up until the moment the Spaniard took his medical timeout. So why was Wawrinka able to be so effective where Federer failed? Given their grand-slam tallies sit at 17 and 1 respectively, even a weakened Federer is still at a similar ability level to Wawrinka on the court. This was a victory of ideas, not merely of playing quality. Where Federer took the court looking largely directionless Wawrinka was a man with purpose. So let’s take a look at the matches, and highlight the key differences between the two Swiss men in their tactics.

Looking For Patterns

I’ve often drawn the analogy that high level tennis is played like chess. Genuinely unforced errors become a relative rarity – instead the players are competing for position. Underlying all of this is the importance of patterns. Patterns are everywhere in every sport, and all top athletes employ them. In American Football, they have set plays, with names. In what the rest of the world calls “Football” (and Australians and Americans call “Soccer”) even in the seeming madness there are techniques, combinations and patterns that the teammates have done together countless times. The defenders move (hopefully) with a level of coordination that isn’t always obvious to the casual observer. These patterns exist because, as humans, we get tend to get better and better at things the more that we do them. In the realm of sport, familiarity doesn’t breed contempt: it breeds competence and confidence. We tend to do what we know, and what we know well we do well.

When there are marked contrasts in styles, these patterns become more important than ever as the two players compete not just for points, but to impose their own style of play upon their opponent. An obvious example is Rafter-Agassi, a riveting matchup that produced some amazing matches. Agassi couldn’t hope to volley like Rafter, and Rafter couldn’t hope to outhit Agassi from the ground over the course of three or five sets. So, they each struggled to impose their game. Rafter serve and volleyed, forcing Agassi to attempt the pass. Then on his own games, Agassi would keep the ball deep, and try to prevent Rafter from coming into the net. In these two matchups things are somewhat different. All of these players like to finish points with their forehands (yes, even Stan “The Backhand” Wawrinka!) and given Nadal’s left-handedness it becomes a battle to see who can create more positive forehand opportunities for themselves.

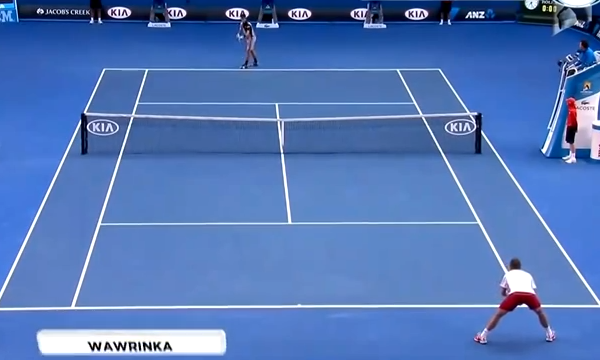

Federer Problem #1: Federer Let Nadal Dictate With His Forehand

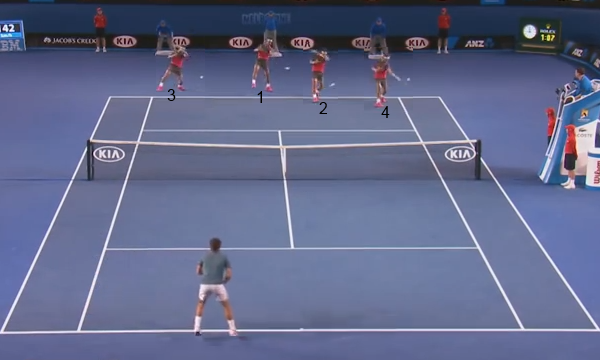

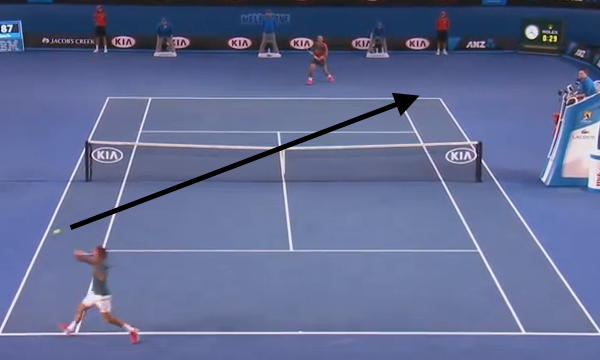

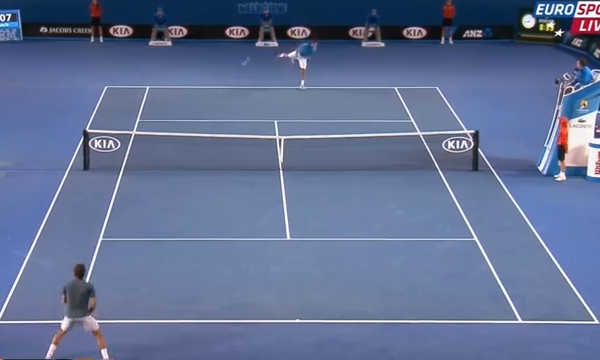

The above image shows the forehands of Nadal in a single point beginning from Federer’s return of serve. Nadal gets to hit the first two from near the center of the court and as a result immediately has Federer on the defense. Indeed Federer was stuck hitting slice backhands for the entire rally after the return, which ended with Nadal hitting a backhand dropshot winner off shot #5. Unfortunately for Federer this is a pattern of play that is all too familiar on Nadal’s serve. Nadal slices a serve into Federer’s backhand, and then proceeds to take Federer’s fairly central, low-pace return and pound him into submission. It’s a pattern that Federer has struggled to break against Nadal, and typically once he has hit a couple of defensive slice backhands he is in serious trouble.

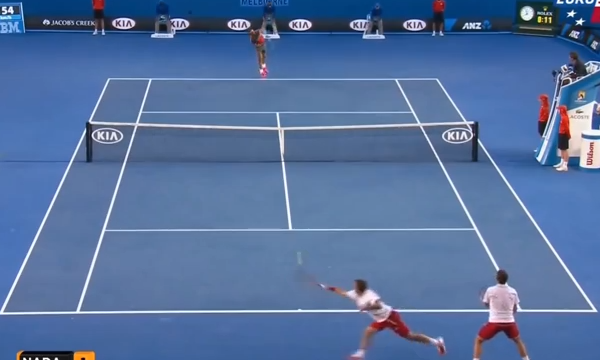

Wawrinka Solution #1: Turn The Tables

One thing Federer has always struggled to do against Nadal is take an appropriate “grinder” mentality. His game can be so mercurial, yet Nadal brings him down to earth with a brutal single-mindedness. Wawrinka has no such compunction. The beauty of his backhand aside, authors have written little about the poetry or grace of Wawrinka’s game. He is a power player and Nadal causes him no identity crisis, as we see below:

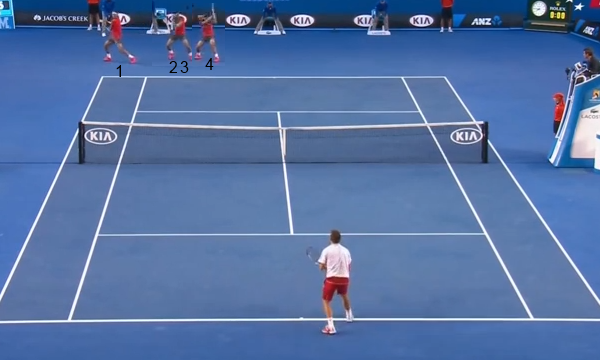

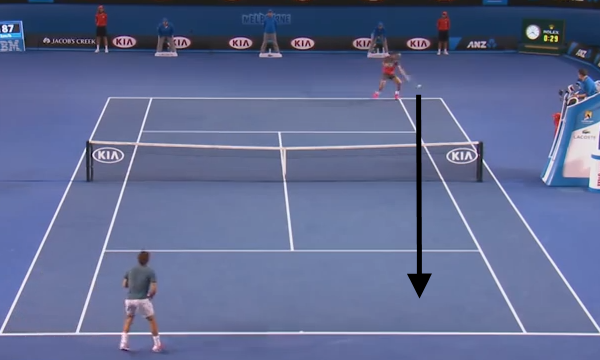

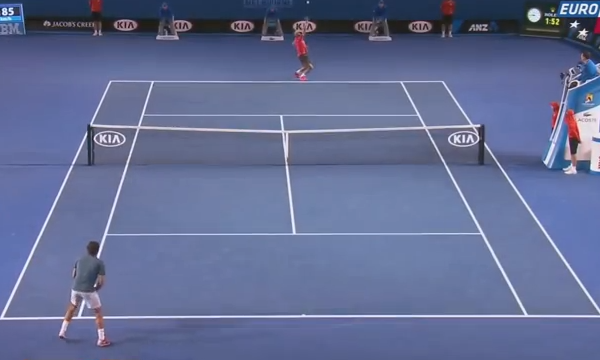

Here we see Wawrinka turning the tables. This sequence of four shots begins with Nadal’s return of serve off a Wawrinka second serve. Ironically I had to use the same Nadal image for shots #2 and #3 in this rally because they were quite literally on top of each other. Desperate to break out of this corner, Nadal takes backhand #4 down the line:

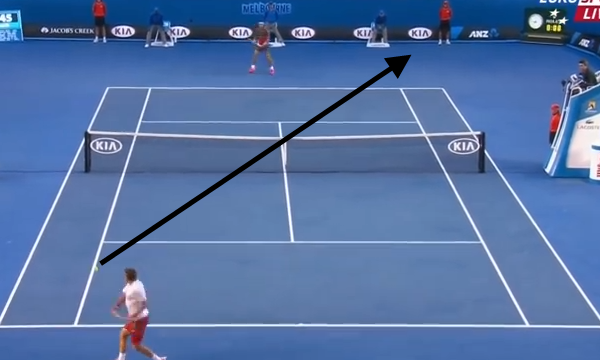

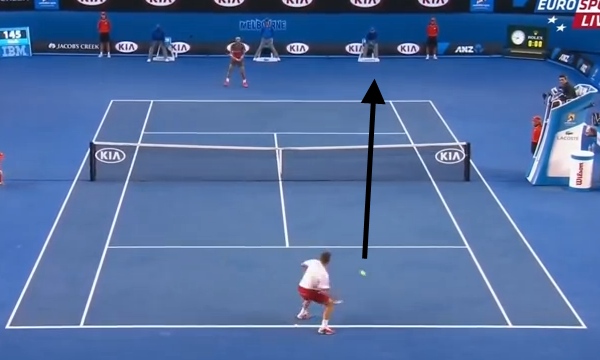

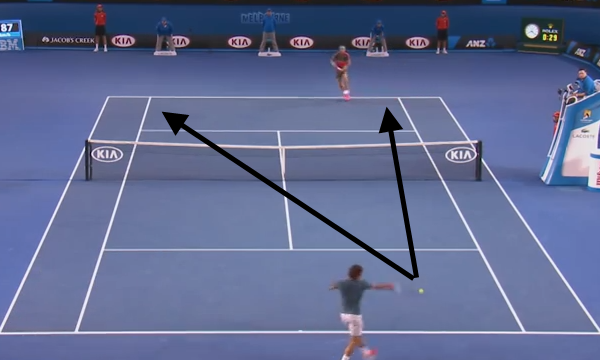

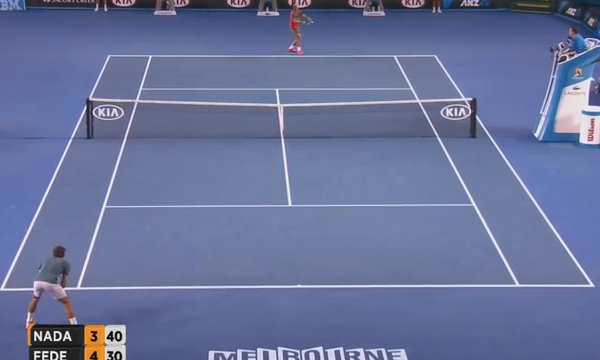

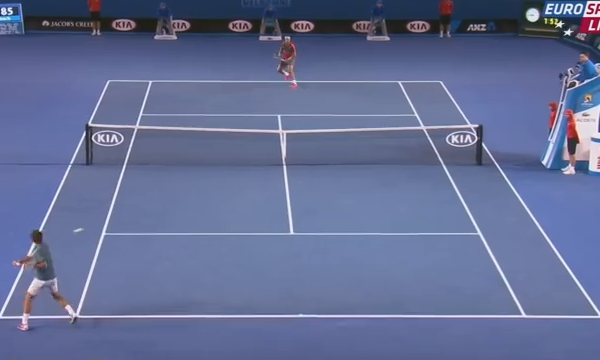

And now Nadal will finally get to hit a forehand. However he isn’t hitting it on his terms, he is hitting it on Wawrinka’s terms. Wawrinka will drive this ball with pace into Nadal’s forehand corner, and Nadal is forced to hit a skidding, defensive ball that he cannot quite get back to Wawrinka’s backhand. The result is that Stan hits another aggressive ball into Rafael’s backhand, then earns this forehand off which Nadal makes an error.

This was a pattern throughout the match: Wawrinka being willing to hit three, four or more forehands in a row into the Nadal backhand. More often than not he waited for Nadal to be the one to change direction, and then he would punish balls into Nadal’s forehand corner. It isn’t that Federer isn’t able to construct this type of point – he did so a few times during the match and won the point almost every time. But rather it didn’t seem a high priority to him – it was not a pattern that he came on court determined to execute. Instead…

Federer Problem #2: Rushing Into The Net

One of the highlights of Federer’s play throughout the tournament leading into this match was his net play. There was a crispness to his movement going forward that showed a marked improvement in this area. Indeed if one can be forgiven the obvious reference, there were shades of Edberg in his prime showing in the way that Federer closed ground to the net to finish points off. However one key element in this has been the timing with which Federer has done so. There has been a patience to the whole process – a sense of waiting for the precise moment. Often times Federer has simply hit an aggressive ground stroke, then only started moving forward when his opponent was clearly off-balance or committed to a defensive shot. Against Murray, who possesses one of the better passing games in tennis, Federer went 49 of 66 (74%) in his net approaches. Against Tsonga he was 34 of 41 (83%) at net.

In his match against Nadal that poise was gone. Rather than wait for the right moment, Federer seemed determined to push forward. Rather than wait until Nadal was genuinely unable to play an aggressive pass, Federer often came in behind forehands hit on or around the baseline. Against lesser athletes this would be a more feasible play given the quality of Federer’s forehand. However Nadal is not just fast, he is strong and explosive. Even in compromised positions, Nadal is able to find stability and attack the ball with spin and power.

Wawrinka Solution #2: Patience is a Virtue

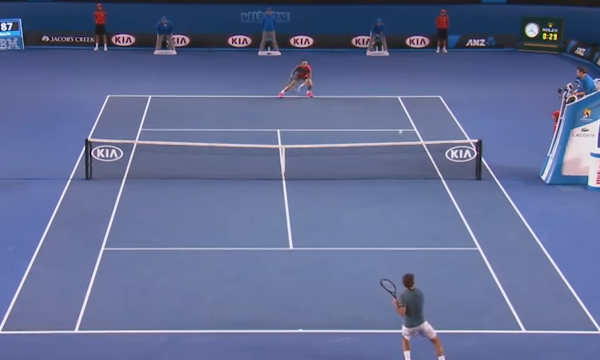

While Wawrinka doesn’t quite have Federer’s net proficiency he’s no slouch there either – after all, he does have an Olympic gold medal in doubles on his tennis resume. However he seems to have a better understanding of when to take the net against Nadal. On the same ball/court positioning that Federer was hitting approach shots, Wawrinka was far more content to pound another ball into Nadal’s backhand and play for court position. Where Federer came forward 42 times against Nadal, Wawrinka came to net just 12. Where Federer won only 23 of those 42 net points (a 55% success rate), Wawrinka won 11 of his 12 (a 92% success rate).

A lot of this comes back to patterns. Wawrinka had a clear plan for success against Nadal, and coming to the net frequently was not a part of that plan. When Wawrinka got ahead in the point, he knew exactly what he wanted to do. Federer was searching for answers – in his near 10 year rivalry against Nadal he still has not truly found a path to victory that doesn’t just involve playing really, really well.

Federer Problem #3: Backhands Up the Middle

Against some opponents this is actually a good play – by hitting the backhand up the center of the court, you take away the angle making it easier to run around a backhand to hit a forehand. Against Nadal this doesn’t work because Nadal can take his forehand inside out from the center of the court far better than most right handers can do the same with their two-handed backhand. Additionally Nadal generates so much topspin on his forehand that even from the center of the court he can still open up the angle to Federer’s backhand. However rather than show you more pictures of Federer doing the wrong thing, I’m going to touch back to a comment made prior to the match about Federer needing to use his slice to good effect. Here is one example of how he can do so:

In the first image we see Federer hitting his slice backhand. As you can see the ball is above his shoulders, the point at which Federer generally struggles to be as effective with his topspin backhand due to to primary pulling muscle of the deltoid simply not being as strong in the higher plane. However when we hit a slice above the shoulder, the larger latissimus dorsi gets to help out since we are also pulling downwards making us a lot stronger. So, Federer is able to hit this shot with reasonable pace and penetration and create some angle:

Here you can see the ball is in the doubles alley at contact, and down at knee height for Nadal – a less than optimal striking point for Nadal’s forehand stroke. Even more importantly he is having to hit this ball on the run. Meanwhile we can see here Federer is bisecting the probably angles of return already, which means when Nadal is striking the ball, Federer is balanced and ready to react in either direction. Due to his position, his having to hit on the run and the lower contact point Nadal’s forehand is pulled more central than he would like, which leads to…

Federer gets a forehand below shoulder height, standing near the center of the court. He has two good attacking options – to hook the ball cross-court with some angle or to play it back down the line. Nadal is scrambling to reach the point of bisection, and at contact here you can see that he is a good 15 or so feet from being in position. As such his weight is traveling from his left to right in an effort to best be able to cover both of Federer’s options. Note the contrast with the previous frame where Nadal was hitting his forehand. There Federer was balanced and weighted neutrally.

And the finish. Federer goes back down the line, and Nadal is left too off-balance to be able to react. The Federer forehand goes down the line for a winner. This was all made possible because Federer opened the court up to the Nadal forehand in a way that prevented Nadal from being able to attack him. It isn’t that Federer needs to do this with a slice backhand specifically – Wawrinka did through most of his match with Nadal using his topspin backhand. However when you watch this match Federer had plenty of opportunities to drive balls wide to Nadal’s forehand and he failed to do so. Whether that’s a question of intent, or an inability to do so only Federer can say.

Federer Problem #4: Returning the Nadal Serve

When you’re only winning 27% of return points against your opponent’s first serve things aren’t going well. When you’re only winning 27% against their second serve, well… things are going horribly wrong. That’s exactly what happened to Federer against Nadal in a continuation of his long-standing inability to do anything with the Spaniard’s delivery. Nadal won 73% on his first serves, and 73% on his second serves. Allow that to sink in a moment. It didn’t matter whether Nadal made his first serve or not – he was just as likely to win the point hitting a second serve. In comparison, against Wawrinka Nadal won only 60% of his first serve points and a mere 42% of his second serve points. Why is that?

Nadal’s serve has a lot of movement on it. In fact, some rough measurements showed me that from the bounce to hitting the back wall it’s got some 4-5 feet of sideways movement. That’s a lot. The end result of this is that Nadal can slide the ball into Federer’s backhand in such a way that makes it incredibly difficult to run around it. So, he’s practically guaranteed that Federer is stuck hitting a backhand return. Add to this the fact that Nadal is good at making Federer stretch in order to hit said backhand return and you’ve got a setup that’s difficult for Federer. We’ve seen Federer flick some amazing passing shots over the years off his one-handed backhand while stretched and on the run. However the return is different. For one he’s not on the run so he has less momentum behind him. Secondly getting the ball past someone at the net doesn’t require pace as much as it does placement. Stretched off the return Federer struggles to generate pace. As a result his returns frequently fall short, and Nadal is immediately in control of the point.

It is in this regard, more than any other, we have ample evidence of Federer’s absurd unwillingness to change even a losing strategy when playing Nadal. Adjusting where you are standing in order to adapt to your opponent’s serve may not be Tennis 101, but it certainly should be standard fare for one of the greatest players in history. Doing so when your opponent’s service location is utterly predictable is just common sense. To put it in perspective, on the deuce court Nadal hit 3 first serves at the body, and 25 down the T to Federer’s backhand. Number of serves out wide to Federer’s forehand? 0. Zilch. None. Nada. So let’s take a look at where Federer normally stands to return serve on the deuce court:

First we have Federer returning against Murray.

Then we have Federer returning Tsonga’s serve on the deuce court.

Now Murray split his deuce court serves between wide and T 50-50. Tsonga served 9 wide serves and 12 T serves during the match. Now it isn’t as though Federer has never played Nadal before. Prior to this match they had faced off 32 times. Surely, given the huge preponderance of serves going to the backhand Federer would make some adjustments from the beginning of the match…

Or perhaps not. As we can see, we’re a little over halfway through the first set. Nadal has yet to hit a single serve to Federer’s forehand on the deuce court and Federer is standing perhaps 2-3 inches to the left from his normal receiving position. What about on the ad court? First we have Federer waiting to return on the ad court against Murray.

And then there is Tsonga…

And finally against Nadal.

And once again we see a relocation measured in inches rather than feet. Certainly Federer takes a small hop to his left once Nadal tosses the ball, but he does nothing to actually deter Nadal from pursuing his chosen course. Now I wish I could say that we see Federer adapt over the course of the match – not an unreasonable hope for such a talented player. And yet, Federer has failed to make a real adjustment to Nadal’s serve across his entire career, let alone the course of a single match. We do see Federer try a couple of different things. Early in the first set, he actually runs around a Nadal serve on the ad court and hits a clean winner with his forehand. I can’t recall if he actually attempts a second time during the entire match, but one would think this would surely be a play worth trying a lot if it met with some success.

Federer also tries standing further back, a rather thoughtless play against someone who is serving at relatively low place and focusing on the angles. In fact this is exactly the opposite advice a good coach gives to a player who has an opponent serving the way Nadal does during this match. Why? Let’s take a look…

Here we see Federer has backed up, and moved slightly wider. This is an appropriate adjustment to make against an opponent who is serving with great pace but without a lot of angle on their serve. Unfortunately for Federer, Nadal is doing the opposite and as a result, this is where Federer ends up standing when he makes contact with the return on this serve:

Yes, that is Federer standing with both feet outside the doubles side line attempting a backhand return. It may come as no surprise that Federer failed to win this point. So what should Federer do instead? Oddly enough, Federer did the right thing a handful of times, and to good effect. He stood up closer to the court, stepped in and cut off the angle before he was pulled too wide. Below is an example of Federer’s position on contact when he did so:

It’s quick to see that his court positioning is significantly better here than in the previous image. Hitting from higher in the court means Nadal has less time to recover from his serve, and Federer has a much shorter distance to travel to be in good position for the next ball. However he did this a scant few times as a whole, and generally stayed with the same, weakly bunted backhand return for most of the match.

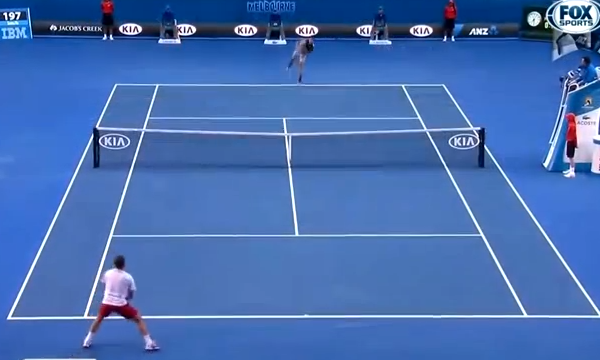

Wawrinka Solution #4?: A Mixture

It’s a little disingenuous to refer to this one as a “Wawrinka Solution” for a few reasons, but we’ll get into those briefly. First, let’s take a look at where Wawrinka stands to return Nadal’s serve at the start of the match and compare it to his normal return positions. We’ll start with Wawrinka’s return position against Djokovic on the deuce court:

So where does he stand to start the match against Nadal on the same side?

We can see that Wawrinka has shifted somewhat to his left, and is also standing a little deeper than he does against Djokovic. Similar to what we saw with Federer, this puts Stan on the stretch as the ball has more time to move and cut away from him due to his deeper position.

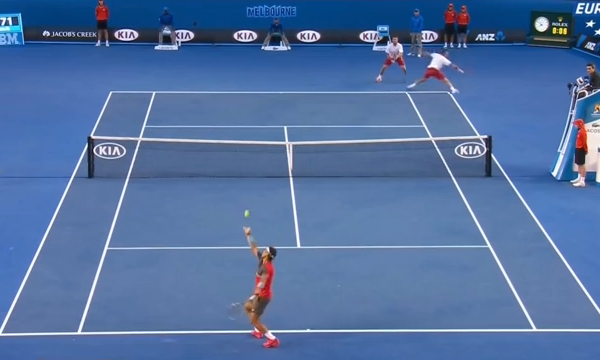

So how about on the ad court? Let’s see where Wawrinka stands to return against Djokovic on that side:

Fairly standard fare. So where does he stand to return Nadal’s serve on the ad court?

Wait a second. We see here that Wawrinka’s taken up much the same position as he did against Djokovic, and is getting stretched out in the same manner that Federer was. So what gives? Why is Wawrinka’s positioning getting him breaks where Federer failed to? For starters, Nadal serves completely differently against Wawrinka than he does against Federer. Remember how Federer didn’t get a single serve to the forehand on the deuce court? Nadal served 11 – eleven – out to Wawrinka’s forehand on that side. And the ad court? Sit down, because whereas only 14% of Nadal’s ad-court serves were down the T against Federer, 37% of Nadal’s serves went there against Wawrinka (with 37% going wide and the rest at the body).

Given these serving patterns, Wawrinka was right to hold something very close to his normal lateral position against Nadal. So how did he get the break? The first break, at 2-1 in the first set was entirely Nadal’s doing. The opening point of his second service game, Nadal stretched Wawrinka down the T (it’s actually the deuce court return image above), got a short, weak reply and hit a poor drop-shot off it that Wawrinka then passed him on. Then at 15-30, Nadal served wide into the ad court, got another weak reply and after coming into the net hit a poorly played backhand drop volley instead of punching it into the open court for a winner. Wawrinka again ran the ball down and drove a passing shot that Nadal couldn’t return. Then finally on break point Wawrinka ran around a body serve to hit a solid top-spin forehand return. However it was solid, not spectacular. Wawrinka started the point neutral, not ahead, and it was only through superior pattern play (namely breaking down Nadal’s backhand) that he clinched the break.

As the match progressed, Wawrinka showed a willingness to move aggressively to his left after Nadal’s ball toss, particularly on second serves. However on the ad side this availed him little as he was still stuck far outside the sidelines making his return. He had much better success when he stepped forward to cut off the angle and sliced a deep return. This put him in an improved court position. The truly key element here though is Wawrinka’s ability to win neutral points with Nadal, be it on his own serve or when returning.

Federer Must Find New Patterns Against Nadal

In truth Federer’s quality of return wasn’t noticeably better or worse than Wawrinka’s as a whole. The issue for Federer is that with the current patterns he employs against Nadal he has no way to win an appropriate number of neutral points to win the match. This is why his return positioning becomes a big deal – he needs to be on offense against Nadal to stand a reasonable chance. Against virtually all other opponents, Federer can start the return points neutral, or even slightly behind, and then use his patterns of play to progress to a position where he has a good chance of winning the point. Against Nadal that transition just doesn’t happen often enough. He truly needs to come at this from two directions. The first is to adjust his positioning on the serve and be willing to take more risks. The second is he needs to fundamentally change his goals when he takes the court against Nadal.

How? He must be willing to grind forehands into the Nadal backhand – a pattern that gives him good success against the Spaniard. He needs to open up the court to Nadal’s forehand, either flattening his topspin backhand out a bit or using a more aggressive slice to do so. And finally he needs to stop pressing his way into the net. Against Nadal he must only come forward when he’s got a truly short ball, or he’s seen Nadal already commit to a defense slice. Nadal is truly one of the all-time greats. Even doing everything right you simply cannot beat him every time. However with these adjustments Federer could at least begin winning his fair share.

What’s Next For Wawrinka?

This is the breakthrough that Wawrinka fans have been waiting for. “Stan the Man” has long had the tools to be a force at or near the top of the game, but a little untidiness in his play has seen him lingering most in the 10-30 range for a while. It’s telling that he’s bounced from being a top 10 player all the way down to the high 20’s, then back again… multiple times. When he plays with confidence and makes good decisions he has the sheer firepower to bludgeon his way through to the late stages of most draws. He really needs to take a page out of Agassi’s book, understanding that he can outhit most players in cross-court rallies and so be willing to do so. If he continues to play with the same discipline and belief that he showed in Australia, he’ll continue to be true factor on the big stage. The so-called “Big Four” is cracked at the seam, and nature abhors a vacuum.