Dimensions of the Court

Too often people play tennis without even a cursory understanding of the geometry of the game. Poll even highly skilled collegiate players and they often don’t have a clue about the court’s dimensions. You might think the knowledge purely academic, but it has a very real and practical application when it comes to winning matches. So let’s take a look at a tennis court:

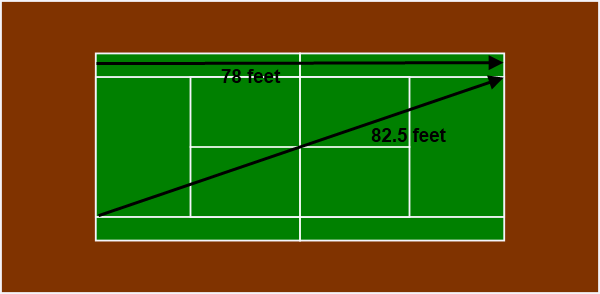

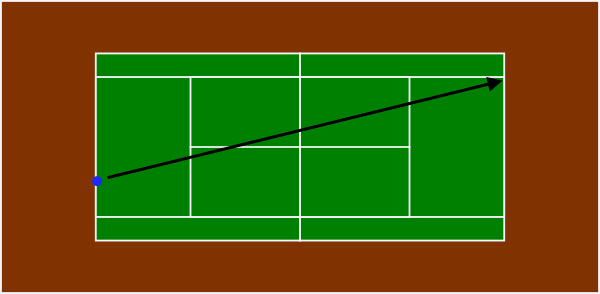

The diagram gives an interest fact. From baseline to baseline on a tennis court is 78 feet. Given that the court is 27 feet wide, some quick geometry tells us that from singles corner to singles corner the court is 82.5 feet. That’s 4.5 extra feet you have to hit into if you hit the ball cross court instead of hitting it down the line. Putting it in those terms can be rather dry, so let’s take a real-life tennis example.

In our scenario, you are in a baseline rally with your opponent. You end up hitting a shot from the center of the court that is straight up the middle, but bounces three inches out (roughly 7.5 centimeters for those using SI units). If you had hit exactly the same shot (same speed, spin and trajectory), but aimed it 10 feet to either side instead, it would have been 3.5 inches inside the line. Hit the same shot 13 feet to either side and it would be in by nine full inches!

But that isn’t all. The net is 42 inches high at the singles sideline, and only 36 inches high in the middle. When we hit the ball cross-court, we hit it over the middle of the net and hence have six full inches less net to hit over. Think of all the times you’ve hit a ball down the line only to have it hit the tape. The exact same shot hit cross-court would clear the net by three inches or more!

Playing Yourself Into Position

The geometrical advantages of playing the ball cross court are hopefully now clear. However that’s not the only advantage to hitting the ball cross-court. One of the poorly understood ideas in doubles and singles is the idea of playing yourself into position. What does this mean? I think we can all easily accept that not all places to stand on a tennis court have equal value. If my opponent is standing in the center of the baseline hitting a forehand, standing outside the singles sideline would be considered poor position. Generally speaking, we want to try to stand in the place that bisects the likely angles of return. Let’s take a look:

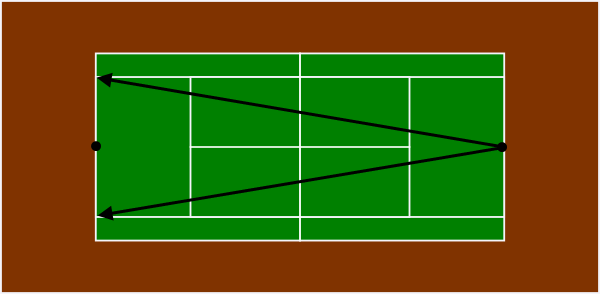

If our opponent is hitting their shot from the center of the court, we can see here the possible angles of return. To be in our best position to get all of the likely shots, we want to bisect these angles (which is a fancy way of saying stand in the middle of them). In this case, that is represented by the black dot on the left side of the court. However once the ball moves out of the center of the court, things change:

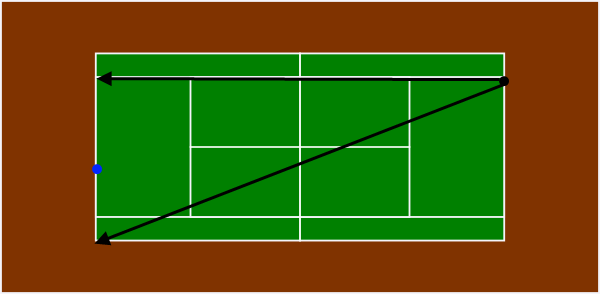

If we move our opponent such that they are hitting from the singles sideline instead, you can see that the angles of return change dramatically. One one side they can play the ball down the line, and on the other, because they are hitting cross-court into the longest part of the court and over the lowest part of the net they can consistently hit a line that extends outside the singles sideline on our side of the court. As a result, to bisect these angles of return we can no longer stand in the middle of our side of the court but instead must shift slightly in the direction of the cross-court ball as indicated by the blue dot on the left side of the court.

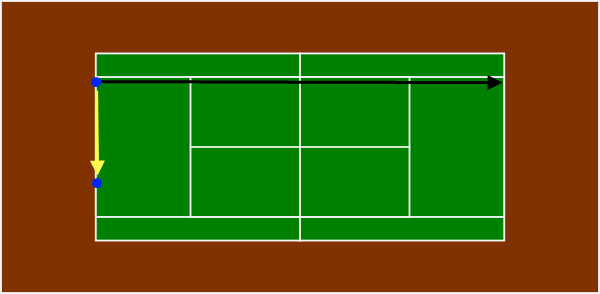

So let’s take a moment and think prior to our opponent hitting the ball. They are going to move to where we hit the ball first. So if I must move to be cross-court from the ball when my opponent strikes it, by playing the ball down the line I actually play myself out of position as follows:

So by hitting down the line as indicated by the black arrow, now we must move to be cross-court from the ball in order to be in the best position. The yellow arrow indicates the required movement in this case. In essence we have voluntarily created a situation where we must run, and very likely hit on the run which is a sure-fire way of increasing the odds of making an error. If we play the ball cross-court instead however:

Now if I begin at the blue dot and play the ball cross-court as shown, I have to move little (if at all) to be in the correct position. Now I can be more balance, I don’t have to turn my hips in either direction and hence it is much harder for my opponent to hit a winner off my shot or to force me into a defensive position.

Conclusion

It isn’t that every shot should be played cross-court. However when you are near the baseline, the vast majority of shots should be hit cross court unless you have a compelling reason to change direction and go down the line. An example of a compelling reason might be an opponent with a fearsome forehand. In this case you may be more likely to win the point by hitting the riskier down-the-line forehand because even though you will make more mistakes doing so denying your opponent the chance to hit forehands makes up for it. Another compelling reason might be if you have caught your opponent far out of position, and if you make your shot down the line you are almost guaranteed to hit a winner or force an error. In this case, again, this might more than make up for the increased chances of you making an error by trying to hit down the line.

However if you’ve struggled in the past to put together effective match plans, stepping onto the court with the idea of hitting all of your groundstrokes cross-court isn’t a bad one. It is certainly better than most of the other plans you could come up with, and is a great foundation. And as in most things, you must learn the rules so that you can learn when to break the rules. So rule #1 is: when near or behind the baseline hit everything cross-court.