In the wake of Nadal’s first-round struggles against German Daniel Brands, the press has raised questions as the press is wont to do. Most of these questions have centered around the dip in form Nadal must have suffered to drop set to a career journeyman such as Brands – indeed Nadal lost as many games in four sets on Monday as he did in the first four rounds last year. Such questions are not merely short-sighted, they show a genuine lack of understanding of just who Nadal is as a tennis player. He has suffered some huge upset losses in his career – Rosol at Wimbledon, Soderling at the French to name just two – and has had some near escapes too. In 2011 John Isner led Nadal two sets to one at Roland Garros before falling to the Spaniard’s will as just one example. But the magnitude of those losses highlights just how good Nadal is – those standing on the peak of the mountain have the furthest to fall. His performances over most of the last decade have been sterling. What can we learn from Nadal’s losses and close misses? How does one take on the Bull on the clay and live to tell about it?

The Magnitude Of The Task At Hand

Nadal’s dominance on clay has officially reached unheard-of heights. He has lost a mere 11 clay court matches in the last 9 years stretching all the way back to 2005. In fact he is more difficult to beat on clay than any player has been on any surface in the Open Era (or perhaps ever). His career win rate on clay of 93% exceeds even Federer’s on grass which is a ‘paltry’ 87.3% in comparison. It is important to highlight this so we understand just what a difficult proposition it is to defeat Nadal on clay. In fact only three men have ever beaten Nadal twice on clay in his entire career – Djokovic, Federer, and former French Open champion Gaston Gaudio. Both of Novak’s victories over the Spaniard came during his amazing run in 2011, and Gaudio’s wins over Nadal happened when Nadal was 16 and 17 years of age.

The Scouting Report From The Bleachers

The skinny on Nadal is that he struggles most against tall, big serving players with big forehands and two-handed backhands. And on paper that makes perfect sense. The two-handed backhand helps to negate the power of Nadal’s high-kicking cross-court forehand. The big serve allows them to put Nadal on the defensive early and use their big forehand to dictate play to his backhand. And lastly the height makes it harder for Nadal to kick the ball up out of their strike zones with his forehand. Many of his biggest losses have come against players who fit some or most of the mold. Robin Soderling, Lukas Rosol, del Potro and the like. However most players these days sport two-handed backhands, and tall guys with big serves and big forehands give everyone trouble when they play well.

So if we accept that Nadal struggling against big serving players with big forehands as nothing to get excited about, are there other matches – either losses or close calls that we can learn from? Is there something deeper?

Digging Deeper

So let’s take a look at Nadal’s career head-to-head versus various players. We of course remove Murray, Federer and Djokovic from the mix – while matchups certainly play a part the level of play all of these players are so complete it is somewhat harder to discern patterns. We also take away the ‘big men’ with big serves and forehands, and lastly remove players like Gaudio whose entire experience against Nadal came when Nadal was 16 or 17. After this, three names leap out at us. Mikael Youhzny, James Blake and Nikolay Davydenko.

Youzhny’s career head to head with Nadal is 4-10. In and of itself nothing to get excited about, but given Nadal’s head to head against most players of Youhzny’s caliber it is a very respectable record. How has he accomplished this? Youzhny has excellent court sense and likes to take the ball on the rise. He also hits a relatively flat, penetrating ball of both wings. Blake not only swung pretty much as hard as he could off both sides, he did so from a fairly advanced court position. This allowed him three wins in seven meetings with the Spaniard. Then there is Davydenko. At 5’10 and 150 lbs soaking wet, one wouldn’t expect him to stand up well to the muscular bull from Spain. However Davydenko doesn’t just hold a winning head to head against Nadal (6-5), he has won four of their last five meetings. Nikolay takes the ball as consistently early as any player in the history of the tour. In fact he is more reluctant to back down and give up ground than anyone I’ve ever seen (including Agassi).

So let’s tie these three in with our earlier information and we come to…

A Question Of Time

“If you give Nadal time, there’s no chance. You have to be aggressive. That’s my view.” – Lukas Rosol, 2012

When we group players that take the ball early on the rise with tall guys with big serves and big forehands, what do they have in common? Time. Whether by position or pace, both types of players steal time from Nadal. And certainly we might say that making your opponent feel rushed is a good thing, and that many players, when rushed, will drop their quality of play. On the other hand, giving some players more time is like giving them rope with which to hang themselves. Some players like a fast pace, others like a slower tempo. Nadal definitely falls into the latter category.

Playing Nadal, especially on clay, is a war of attrition. With his heavy spin and intelligent use of the court Nadal wears his opponents down (although given his intensity on the court perhaps it would be fairer to say he bludgeons them into submission). He is like a boxer who goes to the body, pounding the lungs from his opponent. The only way to combat that is to keep the points short, or if a point is going to be long, be sure that Nadal is the one doing the running. Nadal’s opponents must play first strike tennis to have a true chance against him on the clay. The moment they release control of the point to him the punishment begins.

However attacking from the very beginning changes the tone of the match. Nadal is all too happy to retreat at times, and can end up playing far more defensively than is good for him with a little encouragement. Once he starts playing from deeper and deeper positions behind the baseline, his heavily spun forehand has a tendency to drop shorter in the court, making it even easier for his opponent to control the space. Nadal is an intelligent player, and often makes the necessary adjustments relatively quickly but getting off to that positive, attacking start is critical to have a chance against him.

It is not much of a weakness, all things considered, but then with great players it never is. Federer’s one-handed backhand is genuinely one of the greatest in the history of the game and yet it is still the chink in his armor. So it is with Nadal – rushing Nadal is no guarantee of success, but it is certainly the best shot you’re likely to get.

Attack The Strength

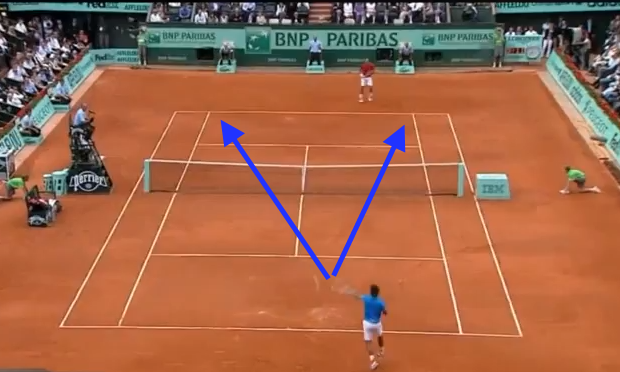

In addition to stealing time from Nadal, you must also attack his forehand. Nadal is at his most dangerous when hitting a forehand from the center of the court laterally. Whether he is behind the baseline, in front of the baseline or on it, the central court position forces opponents to respect his ability to angle balls off in both directions. On clay especially this creates a moment of hesitation as he hits the ball, freezing them in place and costing them a valuable step in getting to the ball.

We prevent this by not being afraid to venture into the lion’s den. It is similar to how one opens up the backhand against Federer – go hard into his forehand corner first, then to the backhand on the next ball. With Nadal however it can be fruitful to go at his forehand for two, three or four consecutive shots. He is more likely to drop balls short off his forehand than his backhand, and with each successive shot Nadal must respect more and more the possibility that the next ball could go into his backhand with aggression. Just as he freezes his opponents with the center-court forehand this in turn freezes him. As an example watch the first point of the video link below:

Believe

“I felt if I can win one set, why not the second one, and then the third one?” – Robin Soderling, 2009

The last step in having a chance to defeat Nadal on clay is belief. By all accounts Nadal as a person seems worthy of respect. However you can respect him as a man and player without allowing that respect to turn into fear. Against most players on clay, Nadal has won before he has even taken the court. His reputation weighs on his opponents, smothers them to the point of despair. Nadal is known for a very aggressive pre-match warmup. He wants to intimidate his opponents before a point is played and hitting the ball hard and with lots of spin during the warmup is one way to do that. Nadal’s amazing record on clay does the rest.

Who among the players on the men’s side truly believes they can beat Nadal at Roland Garros? Djokovic, for a certainty. Youzhny is quirky enough to think he has a shot, and Isner’s past near-upset just might give him the belief. Of course Youzhny and Isner would have to get through Djokovic first. In Nadal’s quarter of the draw there is Davydenko, but for all Davydenko’s winning record against Nadal he has never beaten him on clay and probably wouldn’t expect to here. Jerzy Janowicz has a real shot, if he can get through the hurdles of Wawrinka and Gasquet, and then Gasquet himself could take a crack with that beautiful backhand of his.

All things considered, Nadal received a genuinely tough draw for this tournament. In some years past he’s reached the final without once facing a credible threat but this year he has several. For all that he looks strong and healthy, and far more likely to make the finals of Roland Garros in 2013 than not. A week from Sunday the most probably outcome is Nadal to take the court in the final against his best frenemy, Roger Federer.