In 2006, David Foster Wallace wrote a beautiful piece for the New York Times aptly titled “Roger Federer as a Religious Experience.” It is considered by many to be one of the best pieces of sports writing ever done. In 2006, it simply rang true. Federer was in full flight, at the height of his considerable powers. Watching him play tennis during that time was almost surreal. In every single match he would provide a highlight reel that, years before, would have done for an entire tournament. There seemed to be simply nothing he could not do with a tennis racquet as he blithely hit impossible winners with a flick of his wrist. Those were the early years, the easy years.

Now we know better. It began with Nadal, of course. At first, it was easy to dismiss the inevitable yearly defeat at Roland Garros. Nadal was a clay-court specialist after all, and the kid was pretty good on the dirt. But as Nadal’s game developed, we saw a side of Roger Federer that had seemingly disappeared with the beginning of 2004. Doubt, hesitation, and eventually even a hint of fear. Against Nadal, gone were the broad sweeping groundstrokes and confident finishes. Not entirely, of course. Federer still played with power and grace, but against Nadal he almost always seemed off-balance, unsure of his footing. There were inevitably some marque performances, particularly indoors and on the grass. But as the hard courts slowed, and the grass slowed, we watched Nadal chip away at Federer’s legacy with one buggy-whip forehand to Federer’s backhand after another.

When Nadal took Federer’s Wimbledon crown in 2008, it seemed almost an affront. But as Federer broke down crying on the podium after yet another Grand Slam defeat to Nadal at the Australian Open in 2009, there was almost a sense of inevitability to it. Watching Roger Federer play was no longer a religious experience. It was entirely a human experience.

Federer broke down during the Australian Open trophy presentation in 2009

There was a pattern to their Grand Slam meetings best summarized by their 2006 French Open Final. Federer came out serving sharply, and hitting his sublime forehand with authority. He took the backhand early, and drove it effectively both cross-court and down the line. His timing was impeccable, his instincts moving forward flawless. After a comfortable and commanding first set, the second set opened well enough. Then came the game. Serving at 0-1, Federer opened up a 40-0 lead on his own serve with an easy forehand winner into the open court. He looked set for a routine hold. Federer hit a strong serve up the T, and Nadal chipped a floating backhand return that the linesman called out. In a gesture of sportsmanship, Federer requested the umpire check the mark as he felt it was good (which it was) and the point was replayed. The second time around, Federer netted an easy inside-in forehand for 40-15. Federer pulled Nadal wide with his serve and came into the net for an easy forehand volley into the open court. He missed it. At 40-30, Nadal scrambled and somehow won a cagey point that had both players at the net. Federer netted another routine forehand to hand Nadal a break point, and then saved it with a sharp serve and volley point. A netted easy backhand from Federer, and then Nadal pulled a beautiful backhand passing shot to seal the break on what should have been a routine hold.

Despite being the picture of poise and surety against everyone else, there has always been a sense of fragility when Federer plays Nadal. People usually watched Federer play for the spectacle of it – the result was a foregone conclusion. But against Nadal one couldn’t help but feel nervous, anxious even. Even when he was playing well, one couldn’t shake the feeling that disaster was lurking just around the corner for the Swiss. It wasn’t, ironically the infamous Nadal “heavy topspin ball to the backhand” that was typically Federer’s undoing – that came on Nadal’s service games. Rather it was Federer virtually breaking himself with sloppy forehands and missed easy volleys. Once the lapse happened, the rest of the set/match was spent with Federer bringing inspiring offense again and again, only to be held off by Nadal’s brilliant defense. Break points would come, and come, and go, and go. Nadal would scramble, extend rallies beyond belief and somehow find the amazing pass at the crucial moment until, finally spent, Federer’s chances would fade away into nothing.

The familiar sight of Nadal with the champion’s trophy next to Federer holding the runner-up plate

As 2016 wound down, it seemed the storied history between these two greats had wound down with it. Nadal had missed much of the year with the wrist injury that had forced him to retire from the French Open. Federer took a full 6 months off after Wimbledon, not willing to risk further damage to the knee he had injured in January. Djokovic had hiccuped at the end of the year, but still seemed dominant despite Murray taking Wimbledon, the World Tour Finals, and the World #1 ranking. The next generation of young-guns were finally showing their mettle. Dimitrov came into the Australian Open on a win streak having taken the title in Brisbane (a tournament Nadal played and failed to win). Zverev had climbed to #20 in the world and showed little signs of slowing down. And of course Raonic finished 2016 ranked #3, fighting off a surging Kei Nishikori who came in at #4. It was time to pass the torch, for the next generation to come through.

Nadal and Federer had other ideas. Entering the tournament seeded 9th and 17th respectively, both players moved through the draw with determination. Nadal showed a willingness to adapt, playing more aggressive tennis than we had seen from him since the 2010 US Open. Rafa was standing closer to the baseline, taking the ball earlier and played with a clear intent to move forward and finish points. Meanwhile, Federer displayed a mettle that had previously been missing. In his entire career he’d never before won multiple 5-set matches in a slam and taken the title. After coming through against Nishikori in five, Federer easily dismissed Mischa Zverev before again going five with Wawrinka. As seed after seed dropped before them, Nadal and Federer’s meeting in the final had a sense of destiny about it.

In the end, it came down to courage. Not Nadal’s courage – there has never been any doubt of that. Never in all their Grand Slam meetings has Nadal failed to do his part to create a great match. It is Federer who has so often fallen short. Federer who has wilted, caved, shrunk from the moment. One chipped backhand return after another, we have spent a decade watching Federer fade before his great rival. Not this time.

Federer came out from the beginning playing the style he had used the entire tournament – hitting aggressively off the ground, standing high up in the court and coming forward. Certainly it had its effect on Nadal, who was forced back in the court and put on his heels. Federer wrapped the first set up in tidy fashion, dominating on his own serve and taking his one break opportunity on Nadal’s.

Given the drama that was to come, it is surprising that perhaps the most important game came in the second set – a set that Federer lost. Having gone down a break, and failing to break immediately back, Federer then dropped a second break. The Federer Express seemed headed for a classic derailment. This was the moment – if Federer was to abandon his strategy it was to be now. In the face of a blowout set, Federer kept to the plan. He stayed up on the baseline, hit over his returns and found three forehand winners to break back for 1-4. It wasn’t enough to save the set, but it was enough to keep the faith.

As Federer began to fade in the fourth, one couldn’t help but feel that growing sense of the inevitable. When the fifth set opened, it seemed it was only a matter of time. Nadal broke Federer immediately for 1-0. Federer pushed back, earning two break points in the next game. It was classic Federer-Nadal. Every time Federer got a chance, Nadal came up with some brilliant piece of play and erased it. Nadal 2-0. Federer held at love, and then earned another break chance. Another winner from Nadal. Try as he might Federer just couldn’t break through. Federer held easily again for 2-3, and Nadal stepped up to serve.

On the first point, Federer for once came out ahead after a long rally. He stepped into a high backhand and casually swiped a cross-court winner that Nadal didn’t even run for. At deuce, another cross-court backhand winner. Nadal did run for this one, but to no avail. Courage. When Nadal missed an inside-out forehand wide, the match was level. Federer’s second serve ace at 40-0 saw him back in the lead for the first time in almost an hour.

It has never been Nadal’s way to give his opponent anything – what you get from Nadal you take. The Spaniard found himself down 0-40 in his next service game. With Federer having not lost a point on serve in some 20 minutes, it seemed as though Federer had three virtual match points on his racquet. Nadal saved one break point, then another and another. Federer pushed ahead again with a perfectly hit forehand winner after an incredibly long rally, only for Nadal to level the game yet again. It seemed as though Rafa could keep the match level on will alone. Another long rally, but again Federer got the better of it with a forehand approach that Nadal forced wide.

With Rafael Nadal serving a break point down, at 3-4 in the fifth set of the Australian Open Final, Roger Federer hit the most important backhand return of his life. Nadal spun the ball high and wide, the same serve we’ve seen him hit to Federer a hundred times before. Federer did not slice the backhand. He stepped forward, caught the ball on the doubles sideline and drove it cross-court in a sharp angle. Rafa ran as he always runs, and standing almost a body length outside the court hooked a viciously curving forehand straight into the tape. Break.

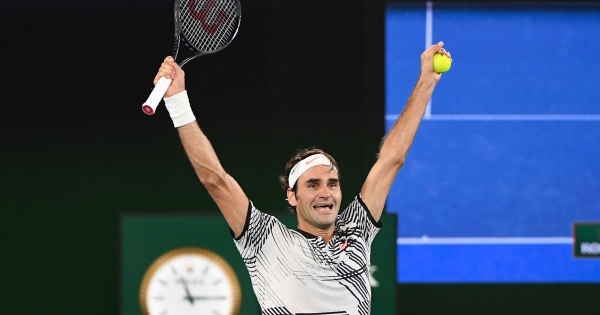

As Nadal’s optimistic challenge on match point failed, the expression on Federer’s face was a complicated one. It was not pure joy, but rather a blend of emotions. Joy of course, but also relief, disbelief, and perhaps, vindication. Maybe it is fitting that the final shot hit in this match was a Federer forehand winner. It is, after all, the shot upon which his career has been built. However it is Federer’s backhand that is a microcosm of his entire rivalry with Nadal. The shot that has been both revered and scorned in turns. The shot that most experts said would inevitably break down. There was never anything technically wrong with the shot, of course. Backhands over the shoulder with 4000 rpms are hard for anyone, whether you hit a one hander or not. It was always about mentality, and belief. In the fifth set, the time when in the past Federer had always been at his weakest against Nadal his backhand was at its best. Of the 14 backhand winners Federer hit on the match, eight of them came in that final set. On this stage, at this moment, Federer stepped into the court and took his shot.

It was never about the stroke. It was always about the courage.