Introduction

Shapovalov is without doubt one of the most entertaining players on the professional tour. His commitment to offense and style frequently make Shapovalov’s matches a spectacle. Despite being of fairly average size and build for a tennis player, Denis produces a huge amount of power with his 6’1 frame. Nowhere is this more evident than in his signature shot – the jumping one-handed backhand.

In our previous article, we started a discussion on power in the one-handed backhand by examining the role (or lack thereof) of the rear leg in power generation. It isn’t enough to dispel old ideas – we must replace them with newer, better ones. Shapovalov’s backhand shows us a mechanism for generating a large amount of power using the legs without even touching the ground – in spite of the jump, not because of it.

The Utility

At a glance, the jumping backhand might seem more style than substance. It’s easy to view it as a flair shot – something hit more for the sake of showing off than winning points. However the jumping backhand as Shapovalov is using it has real utility if you have the ability to execute it.

It allows Shapovalov to hit the ball below his shoulder. Anyone who has watched Nadal play Federer on clay understands that hitting high backhands is hard. By jumping in the air, Shapovalov lowers the height of the ball relative to his body. This means he doesn’t need to wait for the ball to come back down again.

It also takes time away. Since he doesn’t have to wait for the ball to drop, Shapovalov is able to take the ball higher in the court, robbing his opponent of time and space.

We aren’t only examining this shot because it has utility. In learning how Shapovalov is able to generate such power in mid-air, we gain valuable insight that will help us to generate power in most situations on the court.

The Launch

You can’t hit a jumping backhand without jumping. The launch is where many people make mistakes while attempting to hit this shot. Frequently they try to jump off the wrong leg.

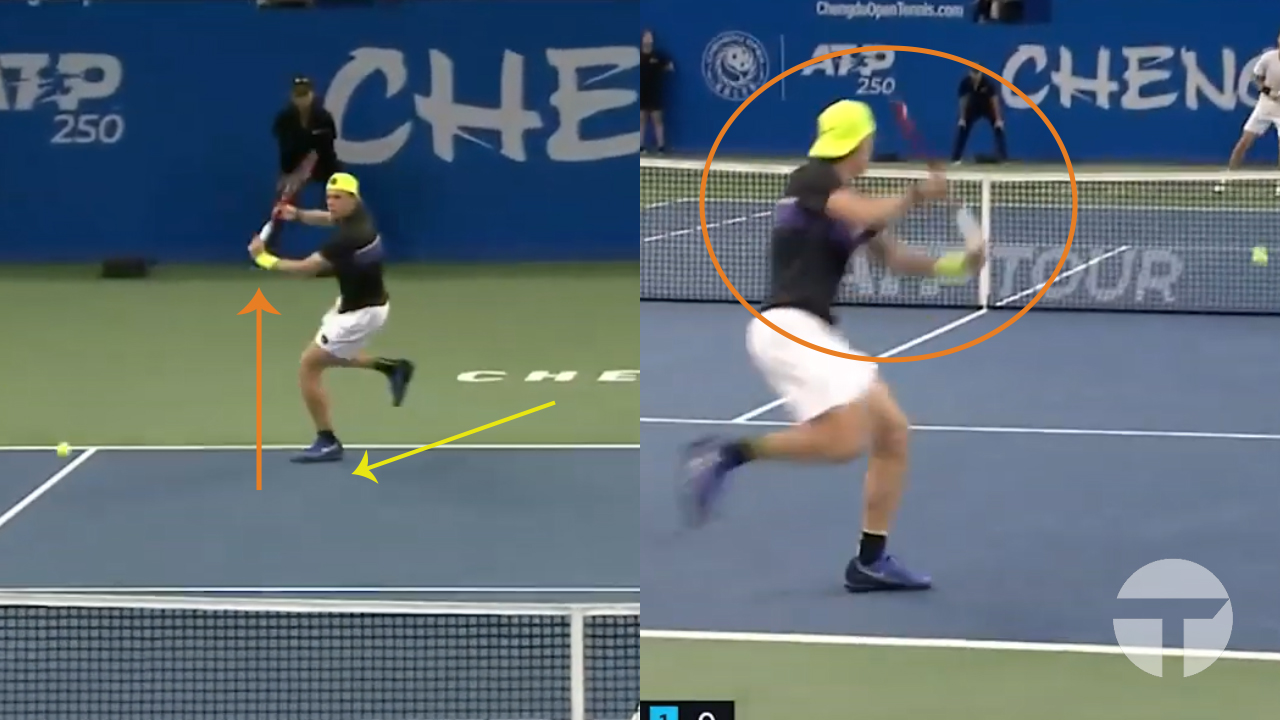

The first step in the jumping backhand is the jump. Remembering that part of the goal is to lower the contact height relative to the shoulder, we have to jump sufficiently high to do this. Shapovalov begins by accelerating towards the ball. What we are aiming to do, besides just getting to the ball, is to convert the forward motion from the running (the yellow arrow) into upwards motion (the orange arrow). The entire time he is moving, Denis is preparing his racquet like he would for any other backhand. His shoulders are turned, his racquet head held high in preparation (as shown to the right).

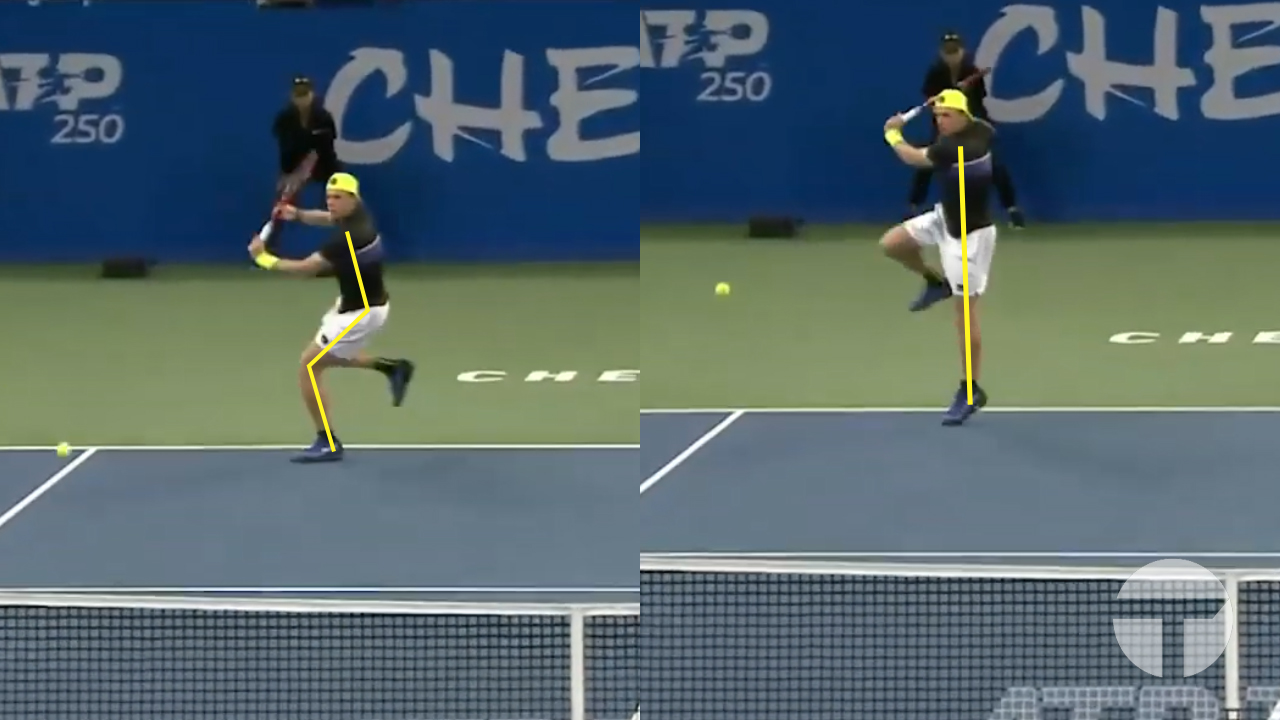

Once he reaches his launch point, Shapovalov lands on what will be his lead (left) leg in a bent position. When executing a movement for power, the more muscles we can effectively recruit, the more power we will get. In the frame on the left, we can see Shapovalov poised for explosion. His left leg is bent at the knee, with the right knee beside it. He is also bent at the hips, too. Everything is primed for upwards movement.

From this position, Shapovalov can recruit a large number of strong muscles towards his jump. Virtually all of the muscles of his left leg will be involved in pushing the knee into extension. It isn’t only his leg however. Denis’ hips are also in flexion. The muscles involved in hip extension will also add to Shapovalov’s upwards drive. When we look to the right frame of the image, we see Shapovalov has extended his left leg and also his left hip.

The right leg is also playing a role here. We can see that Shapovalov swings his right knee up in coordination with the left leg drive to contribute even more energy to the jump. By the frame on the right everything is propelling his body up into the air.

What is the benefit of putting so much energy and effort into jumping high?

There’s a couple of reasons for this. The first is that the higher he jumps, the more options he has. Shapovalov will be in the air for longer, and importantly, he will have more time in which he is on the way up. The easiest time to hit the ball is at the peak of the jump. The most difficult is when you are on the way down.

The higher Denis jumps, the closer to an ideal contact point he is able to create. Most players are able to generate the best combination of power and control at a contact point between waist and shoulder height.

Finally, the higher off the ground Denis is able to take the ball (but lower relative to his shoulder), the better his angles of attack over the net and into the court are.

The Explosion

We can really separate the shot into two separate parts. The first (the launch), is all preparation. We should not confuse the jumping with the hitting. They are not the same thing! Contrary to what many believe, the jump is not directly contributing power to the shot. Rather, the jump is a preparatory action, creating the right conditions in which to hit the shot. The force(s) put into jumping does not contribute to adding power to the shot.

Now that Shapovalov has reached the peak of his jump, we arrive at the second stage of the stroke – the striking of the ball. There remains a popular idea that driving up into a groundstroke is a good source of power. However if groundstrokes are rotational in nature (and they generally are), driving energy upwards doesn’t seem the best strategy. In the previous article we addressed the role (or lack thereof) of the back leg in the one-handed backhand. We established that the rear leg is not providing a significant amount of power to the rotation, as the back foot isn’t pushing off the ground.

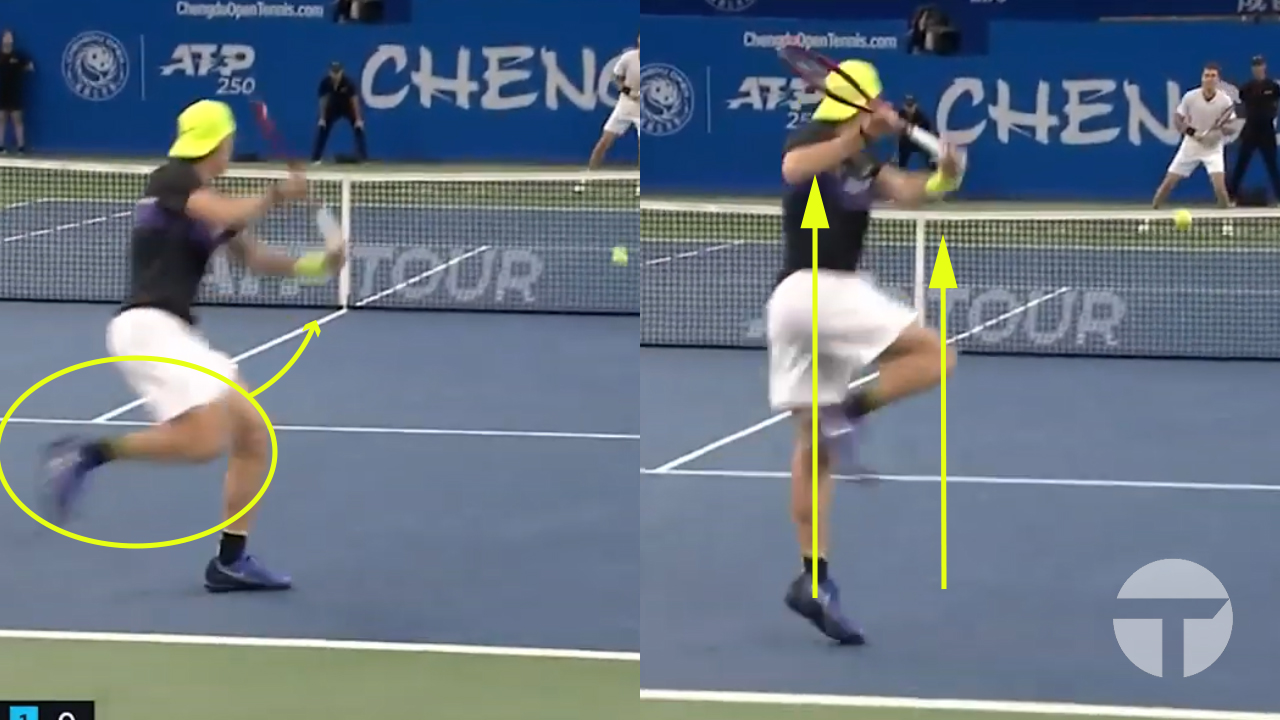

On the left frame we have Shapovalov in the instant he is about to leave the ground. At this moment he is at his maximum upwards velocity. His hip extensors and leg extensors have all fired. From this moment on, Shapovalov is fighting a losing battle against gravity. He will decelerate at roughly 9.81 m/s, until the frame on the right – where he is motionless in the air.

At the moment of contact, every ounce of energy that Shapovalov has put into jumping upwards is spent. None of that energy is going into the hitting of the ball. Yet he is still able to hit the shot with high power.

How can he do so without the ground to push off from?

Using traditional power generation models (“step into the ball” & “load on the rear leg and explode upwards”) this simply shouldn’t be possible.

Shapovalov has been preparing to hit the shot with power at every step of the way.

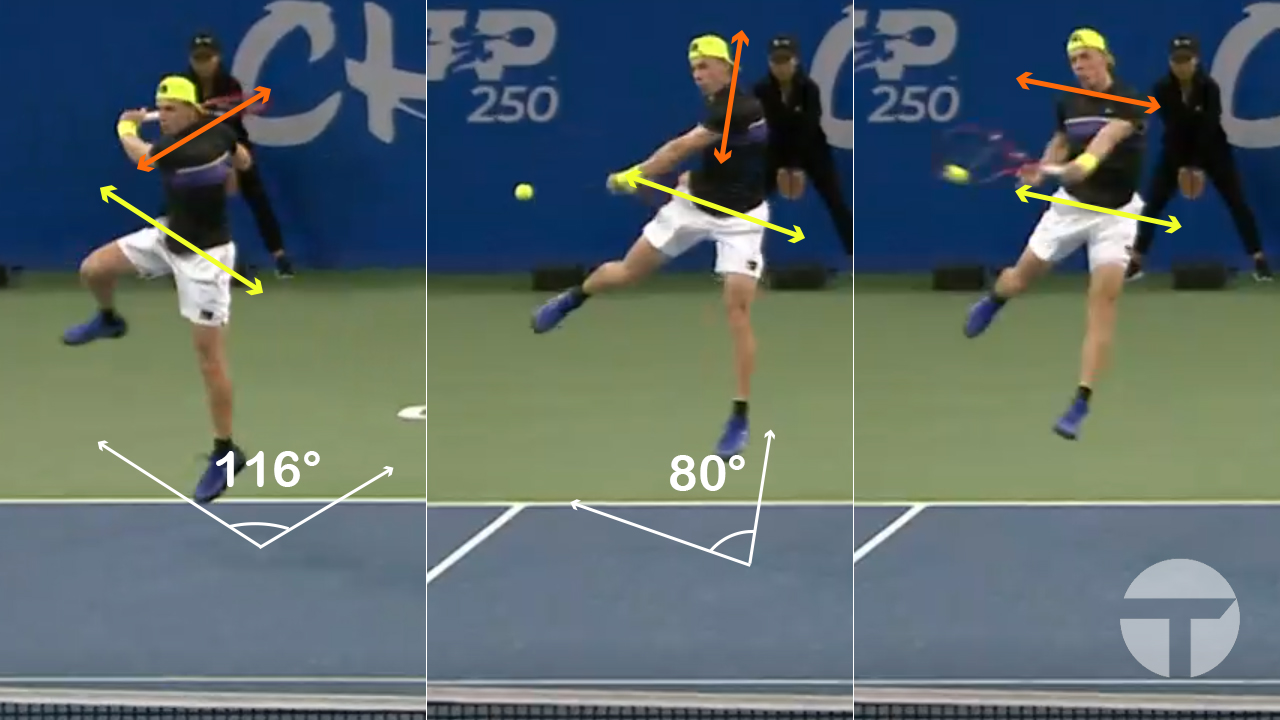

First we look at the position of Shapovalov’s hips and pelvis relative to his shoulders. As he begins his jump, but before he’s begun to accelerate the racquet, Shapovalov has rotated his shoulders significantly further than his hips. The difference appears to be approximately 116 degrees. This provides Denis with two advantages:

By increasing the rotation, he lengthens the acceleration distance of the swing – which means more power

Denis has created a tension line between his hips and his shoulders through his torso. His torso cannot stretch any further around, which means any power applied through his hips will translate efficiently to his shoulders

Shapovalov has also primed himself to use leverage.

Denis can cause a rapid, short-range acceleration of his pelvis using internal and external rotation of his hips. By coordinating the internal rotation of his left hip with the external rotation of his right hip, the two movements work in concert to create an explosive outcome.

In doing so he accelerates a very large mass through a short range of motion very quickly. In this case, the pelvis rotates approximately 13 degrees in the first two frames. As the pelvis accelerates the trunk, the shoulders are pulled around with it – to the tune of 50 degrees!

Since Shapovalov’s shoulders are wider than his hips, they haven’t just traveled through a greater angle – they’ve also traveled significantly more linear distance. Shapovalov has leveraged the movement of his pelvis to drive massive acceleration of the shoulders.

By the time Shapovalov makes contact in the third frame, his shoulders and pelvis are practically aligned. This rotation pulls the arm and racquet through with rapid acceleration. It is a kinetic chain that uses leverage to good advantage. The large muscles surrounding the pelvis engage to initiate the explosive movement. Their effect is magnified by the leverage of Shapovalov’s body alignment at onset. The muscles in the trunk augment with their own energy, followed by the upper back, rear shoulder, and arms. Each step along the way,

Shapovalov adds more and more energy into the shot – but the core of it comes from the pelvic acceleration at the beginning.

The end result is a powerful one-handed backhand hit in mid-air without the ground to use for power.

Braking

The stroke doesn’t end there. Indeed there are still critical elements taking place prior to contact. As in any shot, Shapovalov must create some level of stability to hit the shot with precision. There is also recovery to address, and one more piece of the power puzzle that still remains.

So far we’ve talked extensively about the explosion – the rapid acceleration of the pelvis that initiated the power phase of the stroke. What follows? Stopping the very pelvic rotation that we spent so much of the article examining.

When we looked at how Shapovalov initiated the acceleration of his pelvis in the previous article, it was due to the internal rotation of his left hip combined with the external rotation of his right hip. This coordinated movement rotates Denis’ pelvis in one direction. It should come as no surprise then, that he uses the opposite rotation pattern to stop that rotation.

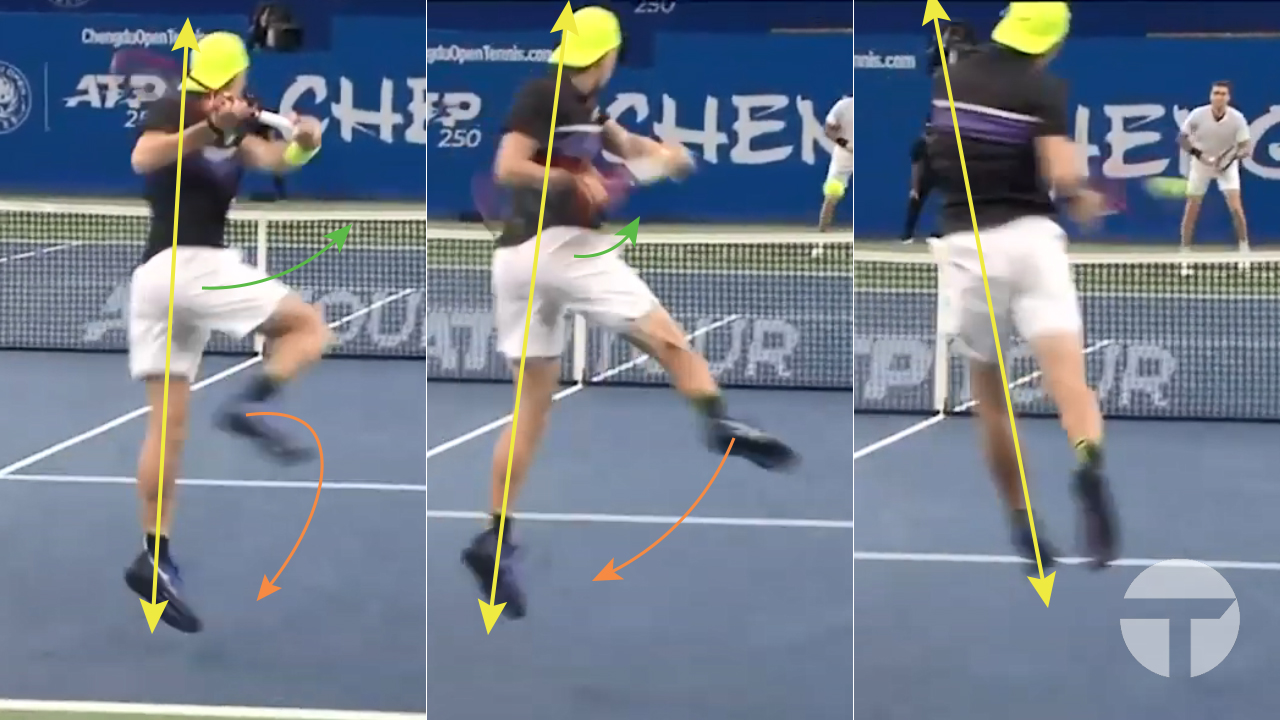

The yellow two-directional arrow represents the axis of rotation of Shapovalov’s body during the stroke. The actual axis is probably closer to his center of mass than this, but the alignment with his body (foot, knee, hip, shoulder) makes a clear visual. As Shapovalov begins to hit the stroke, the pelvis rotates in the direction of the green arrow.

His right leg, however, is going in the opposite direction. The orange arrow shows us the path his right foot will take. He pushes the leg further out to the side as the right side of his pelvis begins to rotate around. Then Denis kicks the right foot backwards, away from the rotation.

This is how Denis stops the pelvic rotation in mid air.

We can see that this backwards movement of the right leg is coordinated with an internal rotation of the right hip. The pelvic rotation was initiated by internal rotation of the left hip & external rotation of the right hip. It is being stopped using internal rotation of the right hip. Why does he do this?

Stabilization

With all of the jumping and rotating that takes place, if Shapovalov did nothing to stabilize his body positions in the air, and stop the rotation of his pelvis at the appropriate moment, then his ability to hit the shot with any kind of consistency and precision would be hindered. Imagine trying to hit a backhand in mid air while your entire body continues to rotate in a circle. There is such a thing as rotating too far.

We see in this sequence how stable the pelvis and trunk are immediate before and through contact. In the first frame the orange arrow shows the movement the right leg will make to finish braking the pelvic rotation. Looking at the yellow arrow, which shows the orientation of the pelvis we see it stays constant even as his arm flies through contact into the follow-through.

In fact, you might notice that by the third frame, Denis’ pelvis has begin to counter-rotate slightly, and is now moving in the opposite direction than it was earlier. Pelvic rotation has crawled to a halt, but the shoulders have traveled a large distance in a very short period of time, launching the arm and racquet at the ball.

The ultimate goal isn’t really counter-rotation however – it is simply to create a moment of stability for contact. Shapovalov needed massive explosion over a very short distance to initiate the kinetic chain, but then also needed stability while actually hitting the ball.

The very same coordination pattern that creates that stability also contributes more power to the shot.

The Whip

Whips are fascinating. A hand moving at a few meters per second can cause the tip of even a short whip to break the sound barrier. One of the reasons this happens is due to conservation of momentum. The whip is at its thickest in the handle, and becomes thinner as it progresses towards the tip.

When the wielder cracks the whip, they begin by moving the hand and then stopping it. This movement travels as a wave down the entire length of the whip. As the wave gets closer and closer to the tip, the mass becomes smaller and smaller. Physics tells us momentum must be conserved. To conserve momentum, the velocity becomes faster and faster.

Backhands follow the laws of physics too! Denis initiates acceleration of the pelvis through internal rotation of his left hip, and external rotation of his right hip. In doing so, he has created momentum in a lot of mass – the entire trunk is rotating with the hips. The goal is to move as much of this momentum into racquet (and hence the ball) as possible. If the pelvis keep moving, then a portion of that momentum stays in the pelvis. So Shapovalov halts the pelvic rotation.

We see in the first two frames the kinetic chain at work. On the left the hips fire, rotating the pelvis (the yellow arrow). By the second frame the pelvis has squared up to the net. The right leg kicks back quickly, halting the movement of the pelvis. The shoulders don’t stop! They rotate ever more quickly now (the light blue arrow), with the arm and racquet coming with them.

In the third phase the shoulders also stop, but the arm keeps moving. Each step of the way greater and greater momentum is building in the arm and the racquet. The physics becomes very complex, but suffice to say not all of the hip and shoulder momentum is going to end up at contact. Some will inevitably be lost along the way, but a large amount of momentum is channeled into the shot. Thinking back to the beginning, Shapovalov used leverage to initiate a powerful rotation (creating momentum). We see now how he has directed it into the ball.

Recovery

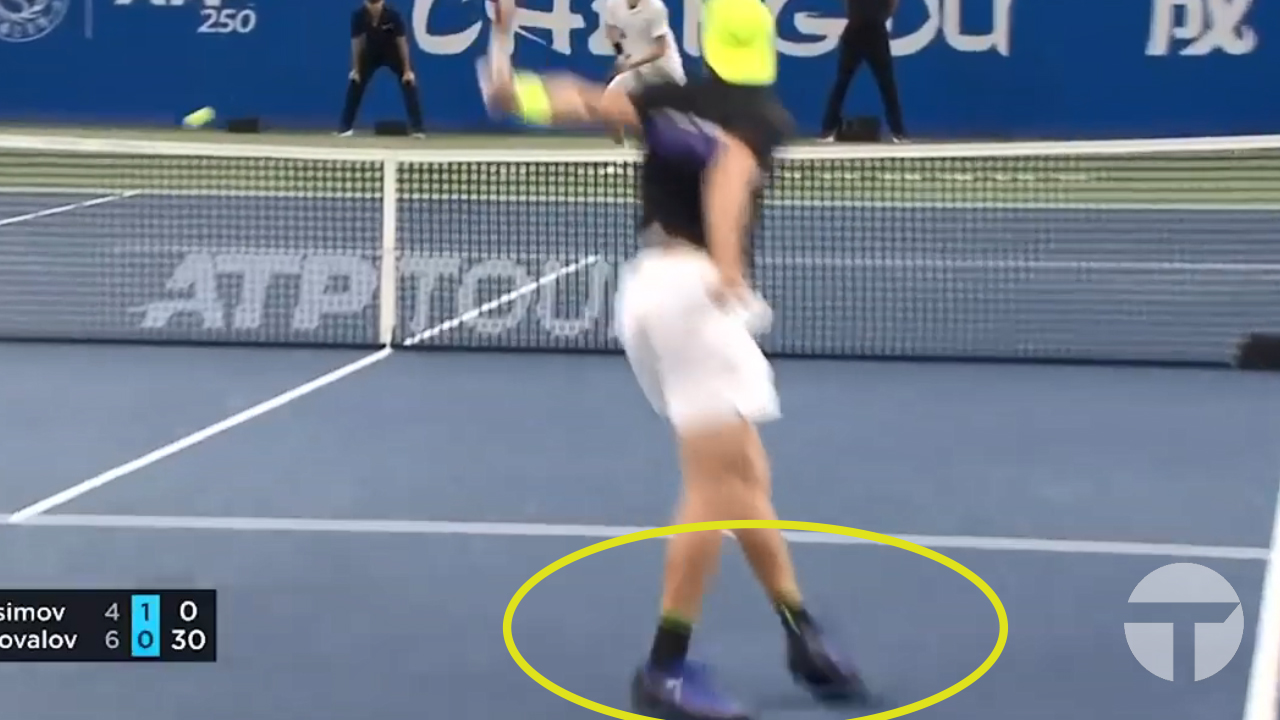

Given the aggression with which Shapovalov hits this shot in matches, we are not convinced that recovery is a primary concern for Denis in the aftermath of the shot. Regardless, an added benefit of braking the pelvic rotation is that Shapovalov will land on the ground in a position that allows for easier recovery. If he did not put a stop to the trunk rotation, Shapovalov would land with his body facing to the side. Not only that, but he would be landing while in a state of rotation – making the landing and subsequent movement momentarily more difficult. What does his landing actually look like?

The position of the feet on landing is far from ideal. It also could be a lot worse. Being athletic, Shapovalov can move out of this position fairly quickly. It is worth noting however that the foot position would be much better if it was a high priority for Shapovalov. An athlete of his caliber could land in a more athletic position, but doing so would mean a shift in the hip/pelvis/leg dynamics – probably compromising some aspects of the shot. It is rarely worth hitting a lower quality shot in order to maximize recovery.

This does suggest however how important the pelvis rotation and counter-rotation is. In order to land more gracefully, Shapovalov would have to either reduce pelvis rotation in the first place (and lose power), or reduce the amount of counter-rotation taking place (and reduce stability). Each of these comes at a price that is probably higher than the value of landing in a better position post-shot.

Conclusion

The paradigms for power generation in tennis have been evolving for decades. Fifty years ago, the majority of players used linear swings on their groundstrokes. Technology and the introduction of biomechanics saw players move to largely rotational models, but artifacts from the old days still linger. “Step into the ball” becomes questionable when players can hit 85 mph one-handed backhands in mid-air.

There is more than one strategy for rapid rotational acceleration. What we see in Shapovalov’s jumping backhand is the predominant strategy being used at the top of the game now – one of pelvis rotation through the internal and external rotation of the hips. We spent the previous article debunking the myth that power must come from the “load and explode” doctrine still used by many coaches today.

This strategy is used in a variety of strokes. Knowing it exists, close examination will reveal it in serves, forehands, backhands, and even the volleys of some familiar faces. We’ve discussed rotational strategies in some podcasts, as well as leverage concepts in our emails. There are a limited number of spaces available for working directly with Tactical Tennis on developing your own game. It is expensive, and only for those serious about investing in their tennis.

Until next time!