We see it in news articles about tennis. We hear it from the mouths of commentators on the TV. Tennis stars of years gone by lament about it. What am I talking about? The effect of technology changes on the game of tennis. Graphite frames? Mono-filament strings? We’ve come a long way from wooden rackets strung with natural gut. Which brings us to the question of today’s article on Tactical Tennis:

What technology has really changed in the last forty years, and what effect has it really had on the game?

The Lag Between Introduction and Evolution

Before we take a look at specifics, let’s talk about something important in the timeline of tennis evolution. A typical professional player starts playing the game somewhere between the ages of 4 and 8. At first they are merely learning the gross motor skills and developing hand-eye coordination. However, when they reach the age of 10-12, they begin development of mature technique. I say begin because it is a process that takes years to complete.

Over this time their strokes really start to take shape. You begin to see the player they will be as an adult. By the time a player reaches the age of 16-18, their technique is mostly developed and solidified. This isn’t to say that they won’t tweak it, or make small changes. However it is extremely rare to see a professional player make large changes to any of their technique in their 20’s with good results.

A classic example of a player continuing to evolve a stroke with small changes is Federer’s service motion. His infamous victory over Sampras at Wimbledon in 2001 showed an immature Federer – although the ball striking ability and major pieces of his game were in place, they were several tweaks away from being the Federer who would go on to win so many Grand Slam titles. The serve is the most glaring example of this. Take a look at the service motion in the two clips below:

However when we’ve seen a player forced to make a more sudden and dramatic change, the results are less than ideal. A clear example would be Sharapova, who drastically changed aspects of her service motion due to shoulder problems. She struggled with her serve for a long time afterwards, and still has never quite regained the quality of serve she used to have.

This is a very important concept: while a player may tweak their technique in small steps over long periods of time, as an adult it is very hard to make large changes and play professional tennis.

So what happens when new technology is introduced to the game? While we see some small immediate benefit to the players currently at the top of the game, it isn’t until a generation that grew up playing with the new technology hits the pro tour that we really see the effect of that technology on the game of tennis. Typically this lag is between 5 and 10 years – the time it takes for a junior who hasn’t fully developed his technique to adopt the technology, and for that technology to become an integral part of the way he plays the game of tennis.

The Starting Point: Wood and Gut

We are only going to look at the advances in technology in tennis related to the last 40-50 years which brings us to our starting point: wooden racket strung with natural gut. So what did one of the old wooden rackets look like? The head size was typically around 65 square inches with the weight falling at a hefty 400g (Bjorn Borg for example had his at 415g).

The heft and small string-bed required players to use very linear swings with the racket head square to contact for a long time before and after hitting the ball. It wasn’t possible to rip up the back of the ball with heavy spin – instead shots were driven with minimal ball rotation.

Along Came Steel – The T2000

The T-2000 was the first major revolution in racket technology that became wide-spread. Invented in the 50’s, and released in 60’s, Billy Jean King became the first player to win a grand slam title with a non-wooden racket with her US Open victory in 1967. Jimmy Connors launched the T2000 into the public consciousness in the 70’s, winning multiple slam titles with his unapologetic brashness.

The T2000 wasn’t any larger than the wooden rackets at 63 square inches, but the biggest shift was in the weight. Coming in a good 40g lighter at approximately 360g, the T2000 was significantly lighter than its predecessors. Although you cannot see the effects in Connor’s game (due to the time lag mentioned above), it did allow a fuller stroke than the wooden frames before it. It’s impact on the game was lessened however by the rapid introduction of graphite frames coming close on its heels.

Prince Patents Oversize

This development arrived just in the nick of time for the upcoming generation of players. In the mid 70’s, Prince patented oversized head frames (then listed as 95-110″). The Prince Classic and Prince Pro followed closely, bumping the frame sizes up past 90″ for the first time. This was followed by a wave of larger-head-sized rackets. Although many would fall in the 80’s, the increase of 40%+ in the stringbed size allowed for players to be much more aggressive in imparting spin on the ball.

We see some effect of the lighter and larger frames on the game of players like Ivan Lendl. Lendl was really the first ‘modern’ player – hitting topspin on both sides with aggressive groundstrokes. Looking at his technique, you can see the direction of the future of tennis – he is the bridge, the missing link, between the 70’s and modern tennis.

Graphite Frames Arrive

The end of the 70’s saw the last true innovation in racket technology arrive – graphite frames. The graphite frames were stiffer than those made of metal, which allowed for more control for highly skilled players. This stiffness, combined with lighter weights and larger racket-head sizes saw the game begin its explosive phase of evolution. The graphite frames allowed more extreme grips, and greater angles of attack on the ball due to the large stringbed. The weight also allowed for longer, more circular strokes that had a greater element of wrist mobility to them.

This moment also ushered in a truly remarkable period of tennis – at the top of the professional game we had two markedly different generations of players. In the older players on the tour we had those who had grown up and learned to play with wooden rackets such as Jimmy Connors and Vitas Gerulaitis. These players hit predominately either with slice or very flat balls with little spin. They are truly products of the technology of their time.

And then we have a generation of players who learned the game with a mixture of the technologies – Lendl, Edberg, Becker, McEnroe. These are players who had grown up first with wooden rackets, pretending to be Rod Laver and John Newcombe. But then, in the early teens they would have had access to steel rackets, and then in their mid teens to graphite frames. Not all of them adopted the same technologies and those that did not all at the same time. McEnroe didn’t switch to a graphite frame until 1983 and you can see the impact on his groundstrokes. Lendl on the other hand was an early adopter of graphite and again the impact on his game is clearly visible.

However it is important to note that none of these players truly learned the game with a graphite frame. The release of graphite rackets was too late for them to have been able to use them except in the relatively late stages of their development. Which brings us to…

The Graphite Generation

Sticking with our 5-10 year span mentioned at the beginning, with the graphite frames coming around 1980 the middle of the 1980’s should have seen the first generation of ‘graphite players’ coming through the ranks. Players who, from the age of 10 or under had access to graphite frames. And so, beginning in the middle of the 80’s we have what I call the “Graphite Generation” – and with them the genuine arrival of modern tennis.

- Thomas Muster, 1985

- Andre Agassi, 1986

- Pete Sampras, 1988

- Michael Change, 1988

- Jim Courier, 1988

- Sergi Bruguera, 1988

And so we arrive at it: string technology. There has been only one true revolution in string technology since natural gut. Yes, companies have spent a great deal of money trying to find replacements for natural gut. They’ve had varying degrees of success, but by the large it has been a battle for either cheaper alternatives, or longer-lasting ones. Then came Luxilon. A polyester, mono-filament string, Luxilon has since had a profound effect on the game, the full effect of which we may not yet have seen. The first iteration of it was released in 1994, but it wasn’t until Gustavo Kuerten used it to win three French Open titles beginning in 1997 that it truly gained attention.

What is it about Luxilon that has had such an impact? The properties of the string are such that it provides good power but, more importantly, increased levels of spin over previous string technologies. However this is where things get interesting. There is surprisingly little scientific information available regarding these strings and their performance. The ITF conducted an independent study and found they created “slightly more” spin. The study performed by Cross and Linsey, resulting in the book Technical Tennis: Racquets, Strings, Balls, Courts, Spin, and Bounce

, found that copolymers like Luxilon offered a 20% increase in spin over a typical nylon string, but only 11% over natural gut.

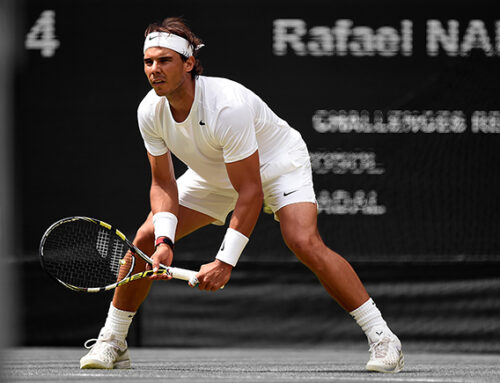

Keeping in mind that most top pros were already using natural gut, if the studies hold true then the impact of copolymer strings on the game may be far less than TV commentators have been telling us for the last few years. While 11% isn’t a tiny amount, neither is it game-changingly large. It certainly significantly outweighs the impact of any changes to actual racket frames in the last twenty years. However to point to strings as the catalyst that has made players like Nadal and Federer possible would be disingenuous.

We can accept that it has impacted the game, but has its full impact been felt? Let’s take a quick look at the time-line. Kuerten wins his first French Open with Luxilon in 1997. It wouldn’t be adopted wide-spread by the tour for several more years. By the mid 2000’s, the vast majority of pros are using a copolymer in at least half their string-bed. Realistically this means top juniors using the string from the early 2000’s. If this estimation holds true, the first players who grew up using copolymers long enough that it could affect or shape their technique should have been turning professional in the late 2000’s – approximately in 2008-2010. Given the depth on the men’s tour, we should start seeing the copolymer generation make their mark in the next 4-5 years.

What will that mark be? How will copolymers shape the game? My current best assertion is: very little. Given the nature of the technology a copolymer string will not have anywhere near the impact on tennis technique that the arrival of graphite rackets did back around 1980. We have already seen the arrival of a generation of players more adept at playing with a higher contact point as a result of increased topspin (see Djokovic’s forehand as a classic example). Will a newer, copolymer generation take the ball higher still? Doubtful. If anything, we might see a generation of players who hit a more penetrating ball with shallower strings, using the advantages of copolymers to create spin not generated by a high angle-of-attack on the ball. But we’ve already seen some of that – Del Potro, Verdasco and Federer (just to name a few) hit a very penetrating ball off the forehand wing. So it might just be that for all the talk (and in some cases complaining), that in the end the strings have had and will have less impact than we all thought.