Tour Patterns: Federer vs Sock (2018 Hopman Cup)

Winning tennis points is all about control – playing the point on your terms. If you are a defensive player, control may mean luring your opponent into increasingly aggressive shots until they make an error. For an aggressive player, it might mean executing serve plus one strategies all day long. Regardless, the true struggle in any match is that for control – for the terms on which points are played.

At one point or another we all find ourselves not in control of the point. What separates good players from great ones, winners from losers is the ability to pivot.

To explore this today we are going to look at two patterns from the 2018 Hopman Cup match between Jack Sock and Roger Federer. Jack Sock represents the archetypal American player – big serve, big forehand, weak backhand. We’ve all played someone like him at some point – running around backhands at every chance, trying to pound away at our own backhand with his inside-out forehand. Federer may represent the archetypal 19-time Grand Slam winner, but the good news is you don’t need to be Roger in order to learn and use today’s tactics.

The Problem

Jack Sock’s forehand isn’t just big – it is by most of the data the biggest forehand on the men’s tour in terms of average ball speed, and among the highest in revolutions per minute (spin). Simply handling the shot is a challenge, and when Sock posts up in his backhand corner and starts pounding you with inside-out forehands it can be very hard to see a way out.

The first pattern we will look at comes from a point when Sock did exactly that. Let’s be clear up front – Federer’s backhand is very good. It’s always been a stellar shot and in 2017 Federer finally unleashed it to the tune of two grand slam wins. For all that, to imagine for a moment that he wants to be hitting his backhand against Jack Sock’s forehand is lunacy. Part of Federer’s success has come not just because he’s got a great forehand, but because he’s done a good job of manipulating play to be able to use his forehand preferentially over his backhand at every opportunity.

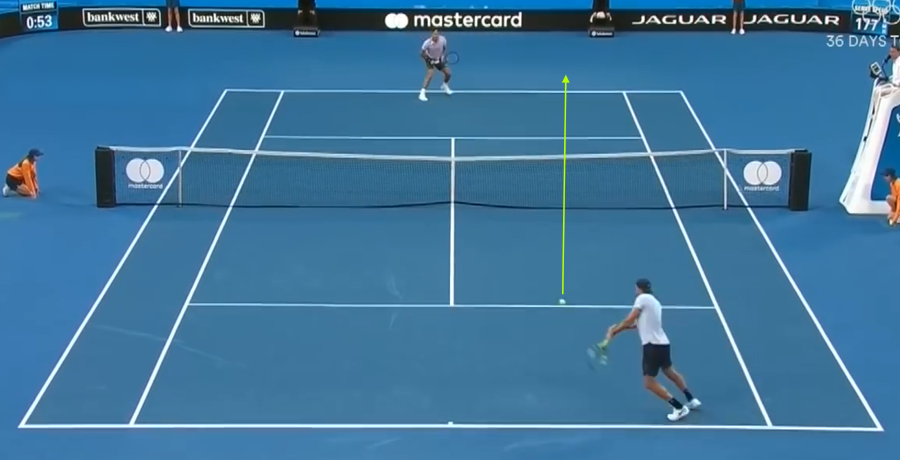

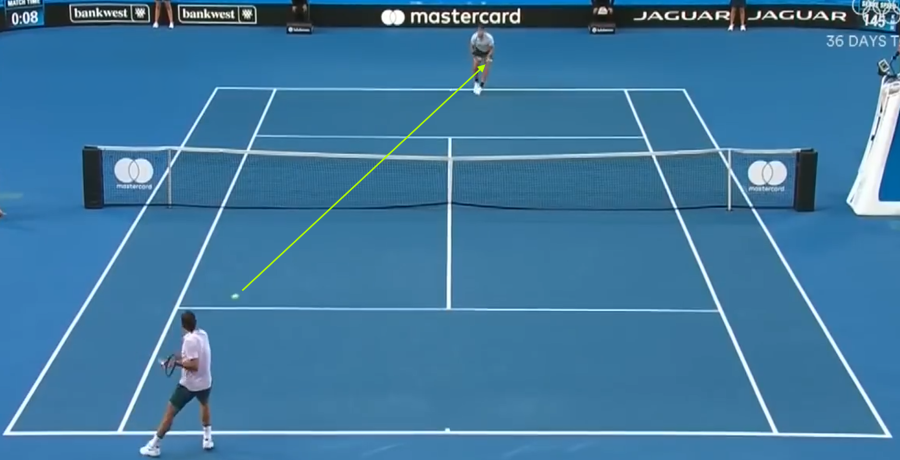

Sock achieves his first goal of the rally right here, getting his return to the Federer backhand. When Roger hits a backhand as his first shot after the serve, statistically his odds of winning the point go down dramatically. Slightly rushed and still a hair off-balance from the serve, Federer hits the ball slightly cross-court.

Jack Sock couldn’t reasonably hope for more than this. Sock’s got a fairly central ball that he can comfortably run around and turn into a forehand. Even better, because it’s a little to the ad side it makes it easier for him to play it into Federer’s backhand. This is leverage. This is what Jack Sock wants in every point he plays against Federer – a forehand on his own terms with the chance to attack the Federer backhand.

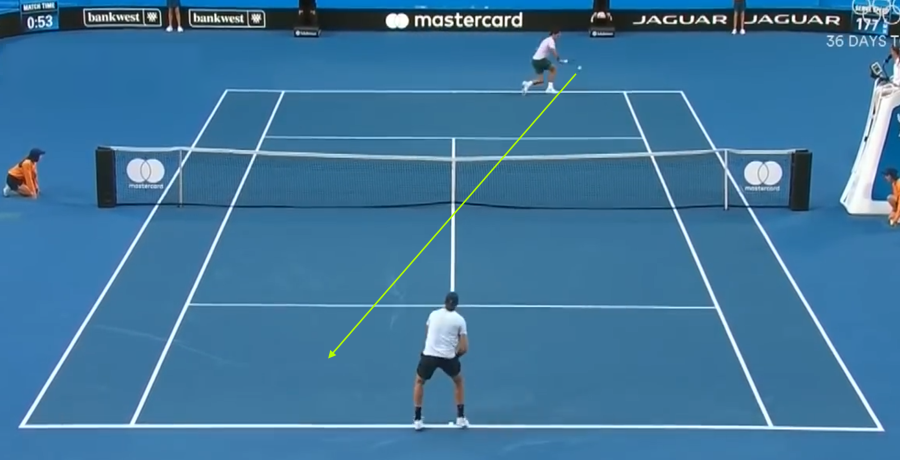

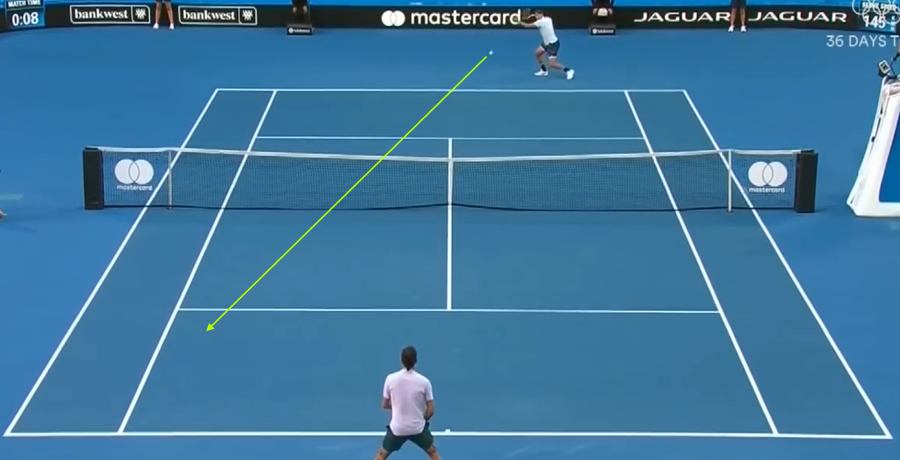

Now comes the game of chicken. Sock’s forehand may be huge, but Federer’s is better. Sock knows as long as he’s got his forehand into the Federer backhand, he has control of the point. The problem is he can’t do this forever. If he doesn’t convert his positional advantage into a genuine point-ending attack, then eventually Federer will find a way out. This means Sock must either take a ball inside-in to Federer’s forehand at some point, or hit a big enough inside-out forehand to force an error.

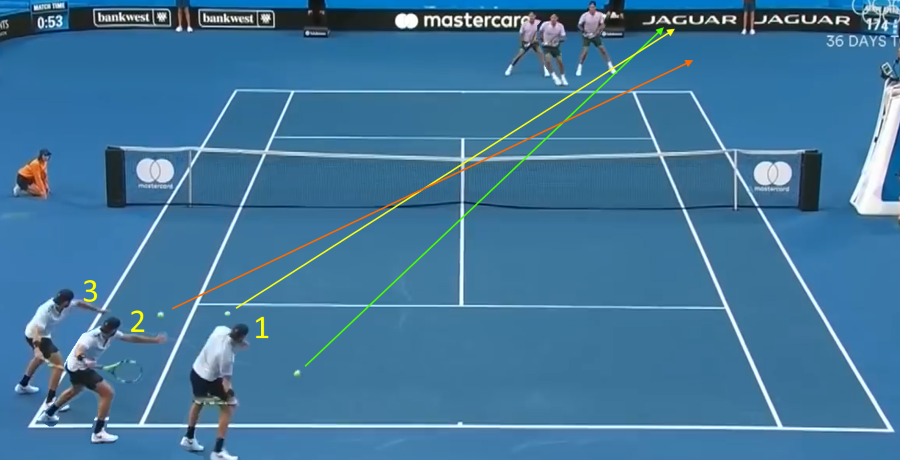

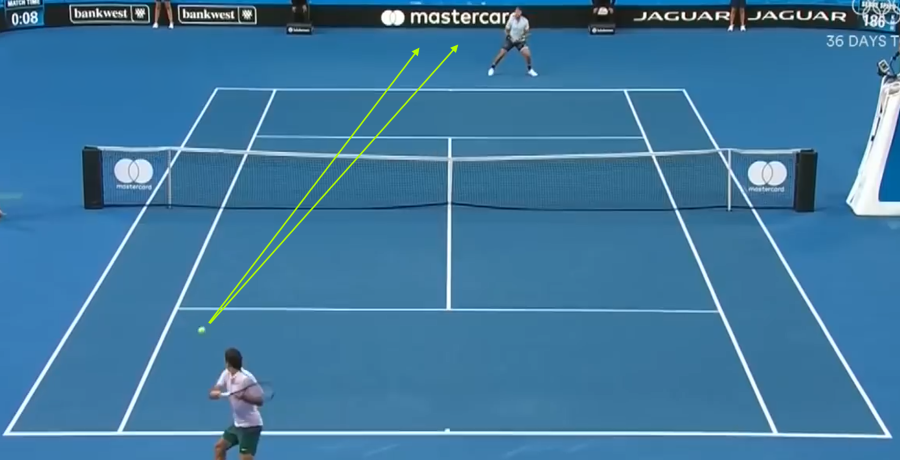

Sock tries for option #2. We can see in this three shot sequence that Jack takes three consecutive forehands into Federer’s backhand, each one a little bigger and better than the one before it. Sock’s positional changes over these three shots shows you how hard Federer is trying to find the Sock backhand. For Federer to take any of these three backhands down the line is extremely risky – the pace and weight of Sock’s forehand makes an error very likely. Roger’s best chance is to get one far enough over that Sock must hit a backhand, and then Roger has a shot at regaining control of the point.

Meanwhile you can see just how difficult it is to get Sock to hit a backhand. By the third forehand he’s standing with most of his body outside the doubles sideline! With each successive ball, the space Federer has to find the Sock backhand gets smaller and smaller. In this point, Federer did eventually find the Sock backhand. Sock waited one shot too long and caught himself out of position, and Federer was able to pivot from defense to offense. However the simple truth is Federer would much rather not be here in the first place. This match is riddled with Sock’s forehand winners, and this point was Sock’s to lose.

When Sock posts into a position like this, both lines are equally viable options for him. Federer can’t lean heavily to the backhand without greatly increasing his chances of giving up the point. Taking away your opponent’s ability to hit two different offensive options is critical to being able to predict, and hence control, play.

Pivoting Play

The more we can restrict our opponent’s offensive options, the better off we are. We’ve seen what happens when we offer Jack Sock angle to work with, but what happens when some of that angle is taken away. Remember one of Federer’s big goals is to redirect play onto his forehand wing. The more forehands he hits, the more likely he is to win the point.

The point begins with Federer hitting a return into a fairly central position on the court. It should be a surprise to nobody that Sock turns this into a forehand, which he immediately takes into the Federer backhand.

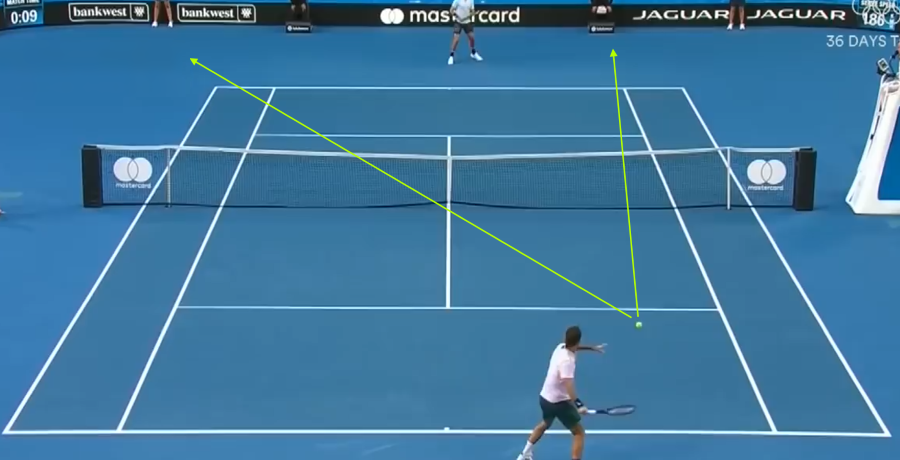

At this point, we’re primed for things to go exactly as they did above. Sock has created the environment he was looking for – the chance to bring his strength to bear on Federer’s (relative) weakness. But Federer didn’t win 19 slam titles by following other people’s patterns constantly(except when playing Nadal!). Roger wants to lure Sock into giving Federer the forehand he so desperately wants. The trick for Federer is doing so without giving Sock too many offensive options. So Federer plays the backhand straight up the center of the court. Not once, not twice, but three times in a row.

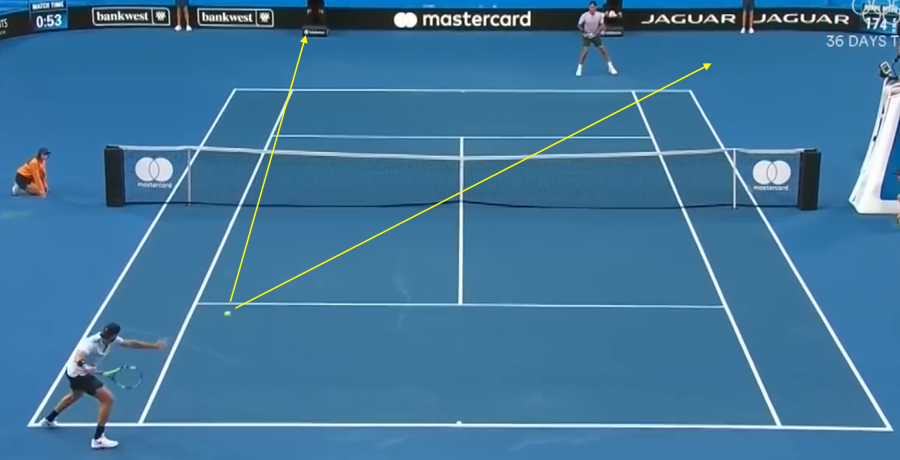

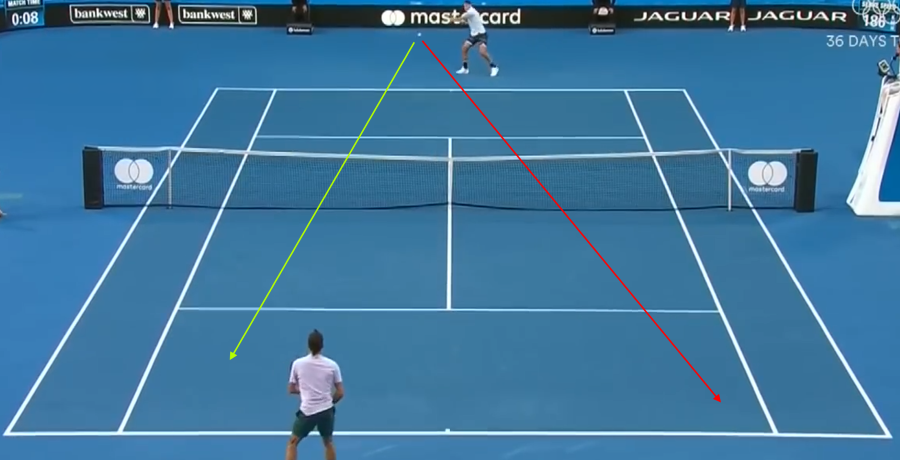

The two green lines represent Federer’s next two shots after the return (which followed an almost identical line itself). Why is Federer so content to put balls into the middle of the court? The answer is because as long as he gets the ball deep enough, in playing the ball up the middle Roger is neutralizing Sock’s forehand. Let’s take a look at Sock’s options off this ball.

When we compare this to the earlier split, we can see that Sock is much less dangerous from this position than he was when he was posted up in his backhand corner. From here Sock cannot spread the court as much, and so Federer doesn’t have as much ground to potentially cover. This lets Federer play a very subtle psychological game here. If we look at Federer’s positioning, he is not in the theoretical ‘ideal’ recovery position when Sock is hitting this forehand. Federer is cheating towards the backhand because Federer wants Sock to hit it into his forehand. Federer is creating the illusion of space, confident he can cover that ground and claim the initiative.

This is why Federer hits three backhands in a row up the middle. It’s a patience game that eventually pays off. On the third forehand, Sock goes into the Federer forehand and not even with any real pace or aggression.

Now Federer has control of the point. Roger can take this ball up the line, or angle it cross-court. Regardless of which option Federer chooses, Sock must be in a position to cover both. Sock cannot predict, and with that Federer has the initiative Now he can pivot from defense to offense.

Conclusion

The important take away here is the pivot. Federer starts the point in a bad pattern – one that puts him at a disadvantage. Given Sock’s commitment to protecting the backhand wing, it is difficult for Federer to hit his way out of the pattern with a cross-court backhand. By taking the ball up the center, Federer is able to shift play onto his own forehand and take control. Key to this is the depth of his backhands up the middle. If Federer had dropped those balls short, Sock would finish the point in a single shot.

You may not be as good as Roger Federer, but the reality is that if you’re not then you probably aren’t playing against Jack Sock. Your backhands might not need to be as deep, or as hard, in order to achieve the same result. The important thing here is the concept. The skill level needed for execution scales with player level, but the ideas are universal. The next time your backhand is getting bullied around the court, or you find an opponent posting up in his or her ad corner to hit the inside-out forehand, try pushing the center to take away the angles. Pivot play onto your own strengths and change the dynamic.