Richard Gasquet possesses one of the most potent and iconic backhands of his generation. On the cover of the French Tennis magazine at aged 9, he was long touted as an up-and-coming future great of the game. In addition to reaching the #1 world ranking as a junior, he won his first ATP title on his 19th birthday shortly after becoming the youngest French player ever to beat the #1 ranked player in the world (Roger Federer). Everything seemed to be coming up roses for the young frenchman. In the years since, his career has been very good without being spectacular. He peaked at #7 in the world back in 2007, has slowly amassed 14 career titles and has made three grand slam semi-final appearances.

His inability to make the impact expected of him on the world stage isn’t necessarily unexpected – only a handful of world junior #1’s reach the pinnacle of the professional game. As everything gets faster and more explosive, flaws in technique and tactics become exposed in a way that they are not in the junior game. We already know that Gasquet possesses one of the best one-handed backhands in the history of the sport. His serve is decent without being particularly good or bad. He’s a competent volleyer. But perhaps from his strokes he’s best known for having one of the oddest looking forehands on the men’s professional tour. It is a glaring weakness in an otherwise good game, which leads us to ask the question: what’s up with Gasquet’s forehand?

I could show this contact point to a thousand tennis coaches, and although each might have minor criticisms based on their own individual philosophies (straight arm vs bent, eastern vs semi-western), all would agree things look just fine. Certainly we could place this image alongside the contact points of famously fabulous forehands like Federer, del Potro and the like and see little difference. This is important, because the underlying problem with Gasquet’s forehand is an underlying problem for many strokes at both the professional and recreational level: how we get there matters.

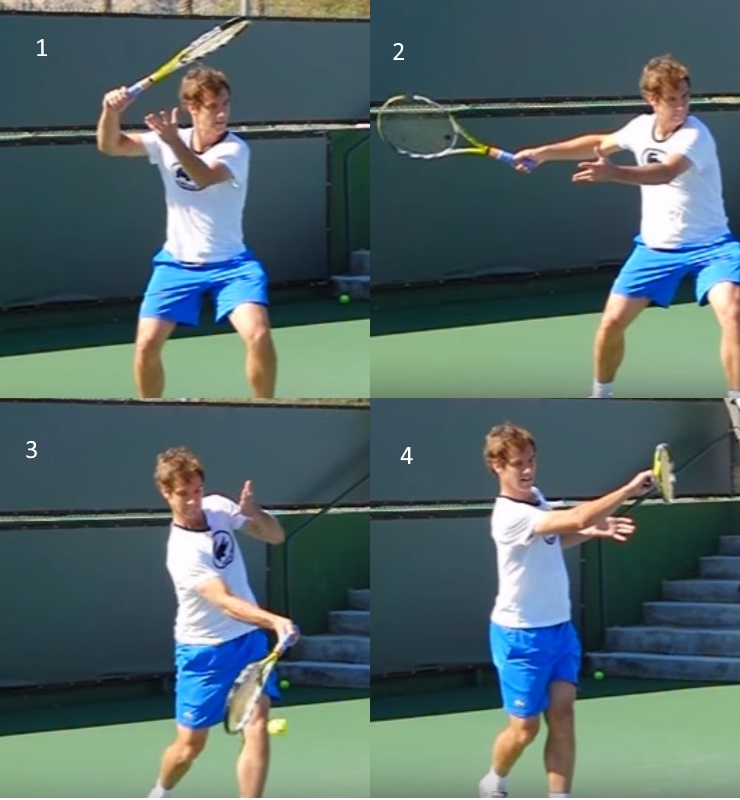

An overview of Gasquet’s forehand

Now we see a fuller view of the stroke. Images 3 and 4 in the sequence look relatively normal – but images 1 and 2 we can quickly see that something is, well, off. This has none of the grace of Federer, nor the promise of brutal explosion of Gonzalez. It just looks a bit weird. In order to break down where things are going wrong, we will talk briefly about Gasquet’s grip, and then compare his forehand to Fernando Verdasco’s to help highlight some of Gasquet’s issues.

Gasquet’s Grip

There is a common belief that Gasquet has a bit of a funky grip on his forehand side. Some people believe he uses a continental grip, but this is not the case. Gasquet is using a fairly classic eastern forehand grip. The eastern forehand grip is undertaught these days, and many coaches use and teach primarily semi-western with this misconception that the semi-western grip provides more spin and power. When we consider that forehand greats such as Federer and del Potro both use eastern forehand grips, hopefully that alone would be enough to dispel such fallacies. Grip is merely a tool, a means to an end. Both eastern and semi-western grips are capable of producing great spin and/or power – it all depends on the rest of the stroke they are used in. In Gasquet’s case, his grip is not at all problematic. However the preparation phase of his stroke, and the way he holds his wrist is.

Preparation Phase

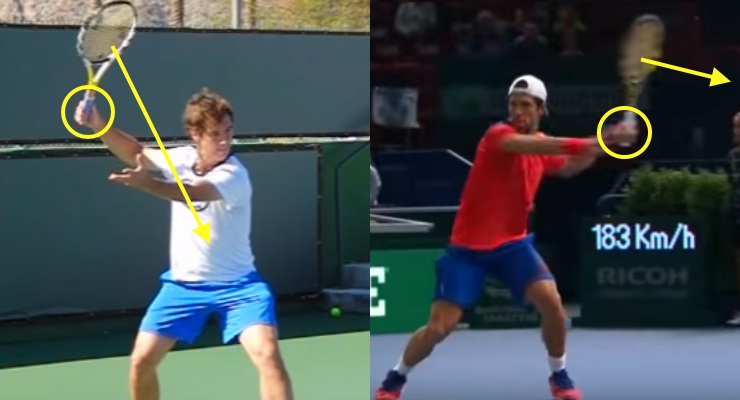

The preparation phases of Gasquet and Verdasco

The image above shows the initial part of preparation for both Gasquet (on the left) and Verdasco (on the right). The first thing I want to note is the similarities between the two. The hips and shoulders are both turned at a comparable rate. Both players are balanced, largely upright. Although Verdasco’s elbow is lower than Gasquet’s this is more a matter of style than superiority. Federer’s elbow is in a similar position to Gasquet’s at this point in the stroke, but high-elbow proponents include del Potro and Gonzalez.

What does matter is the position of the wrist, and the racquet face. The yellow arrows in the image indicate the direction the racquet face is pointing. Given that Verdasco is left handed, and Gasquet is right handed, these arrows should be pointing in almost opposite directions. Verdasco’s racquet face position in this frame is fairly classic for the post-modern forehand. The strings are pointed to the side, away from his body and angled slightly downwards. We would see similar positions with minor variations from Federer, Nadal, and most top-level players at this junction. Gasquet’s position is truly unique. His string-bed isn’t just pointing forward (something del Potro’s does) but also downwards.

This leads Gasquet to the second position in his preparation phase. Again we can we see the strings are still pointing mostly forward and down, where Verdasco’s are facing outwards at this point. When you look at their arm positions, they have converged to a very similar structure from the shoulder through the elbow. However it is the wrist that makes the difference. Whereas Verdasco has rotated his wrist externally, and opened his racquet face to the side, Gasquet has rotated his wrist internally – in the opposite direction it should be at this point. If you think back to the original image of Gasquet’s forehand at contact (and how normal it looked), you can see that his wrist position is very different than it needs to be to reach it’s desired position at contact.

Acceleration Phase

Both players enter the acceleration phase of their stroke

This image captures the moment when both players begin to enter the acceleration phase of their stroke. At this point we can see that Verdasco has begun to lay the wrist back into a position of extension and his forehand is rotated externally. Gasquet meanwhile has a neutral wrist position at best, and appears to still be rotated slightly internally. Verdasco is primed to explode at the ball with minimal changes to wrist and arm position at this point in his swing. This is a stark contrast to Gasquet, who still has to make fairly large adjustments to his wrist, his racquet face, and his forearm!

Both players shortly before contact

We can see that Gasquet is working to catch up now. Shortly before contact his wrist position still isn’t ideal, but it is improving. Verdasco is ready for contact at this point – he merely has to sweep the arm through the ball and it will explode off the racquet with pace and spin. Gasquet is almost there. His wrist is still not fully extended, which means he is still not ready for contact. Here it is important to recognize the velocity of the racquet head. Although both players are a good 15-20 inches (35-45 cm) from contact, that distance will be covered in hundredths of a second at the speed they are swinging at. In other words Gasquet has to finish adjusting his wrist position in a couple hundredths of a second while swinging the racquet at extremely high velocity trying to hit a tennis ball that is coming at him quickly and with spin.

How We Get There Matters

It’s easy to lose track sometimes of how even minor changes in body position can have massive impacts on the mechanics of a swing. If I were to trace the position of Gasquet’s hand through the swing and compared it to the hand position of some of the best forehands in the game there would be a remarkable amount of overlap. Indeed it would be almost impossible to tell the difference between Gasquet and some of the most storied and legendary strokes in the game. However when we trace the position of the racquet head (and particularly where the racquet face is pointing) we would see a completely different story. In this story we see a massive difference that makes obvious to even a casual viewer why Gasquet’s forehand is the weakest link in his game.

And it’s all because of his wrist position.

So much goes into making good contact with the ball. The faster and heavier the ball coming in, the less we can afford to have go wrong in order to reliably make good contact. Gasquet is a phenomenal athlete – his hand-eye coordination is at a level beyond most people’s. That’s what allows him to be a top 20 player despite having a forehand that’s something of a train wreck from a technical perspective. Having the racquet face pointing the right direction at contact simply isn’t enough. Clean preparation that puts us in a position to attack the ball with minimal changes in body position and alignment will improve our chances of making great contact – of getting our desired outcome. In Gasquet’s case, that ship has sailed. At 30 years of age he’s unlikely to make changes to his forehand technique. But maybe it’s time he did.